A hardboiled egg weighs more than a Mountain Pygmy Possum after its hibernation. Image credit: Parks Victoria.

The Mountain Pygmy Possum (Burramys parvus) has an incredible story to tell. The animal weighs as much as a hardboiled egg (at 45 grams) and demonstrates several quirks that no other native marsupial does on the continent. It was initially discovered as a few fragmentary fossils in 1894, but on a frosty morning in August of 1966, the unthinkable happened; a chance discovery brought the fossils back to life. Now, the race is on to bring this critically endangered species back from the brink of extinction, as Parks Victoria and other agencies battle against climate change to protect this “bug-eyed” possum.

Rediscovery

Finding a “thought-to-be-extinct” animal is rare, especially in Australia where the extinction rate is higher than on any other continent. Worldwide, this occurs from time to time: the most famous example of rediscovery was of the Coelacanth, a lobe finned fish that can reach more than two metres in length. Prior to 1938, the last evidence of this bizarre fish was cemented in late Cretaceous sediments, and just like the dinosaurs, were thought to be victims of the mass extinction event over 66 million years ago. But in December of 1938, a Coelacanth was captured by local trawlermen off the coast of South Africa and caused a stir in the scientific community.

In the Victorian alpine/subalpine areas, rediscoveries of extinct flora aren’t uncommon. The critically endangered Mountain Burr-daisy (Calotis pubescens) was thought to be extinct in Victoria but was rediscovered in 2009 from a single location that is now protected by Parks Victoria. The Kiandra Leek Orchid (Prasophyllum retroflexum) is now known from two distinct populations in the subalpine regions in Victoria (and two from NSW), after being thought extinct for more than 80 years.

The threatened Mountain Burr-daisy occurs at only one location, where it is protected by a fenced enclosure, preventing it from being grazed and trampled by feral horses, deer, and pigs. Image credit: Parks Victoria.

But finding an extinct animal known only from the fossil record, alive and breathing, is something else.

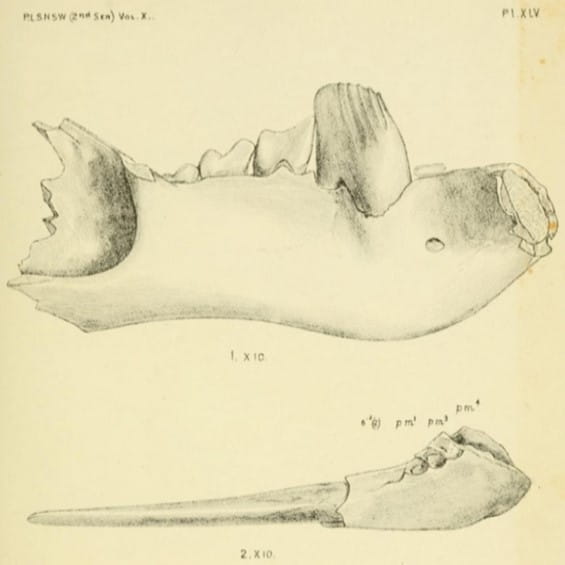

The Mountain Pygmy Possum was first known to western science as a single jawbone cemented in a small limestone block and a few isolated teeth by Robert Bloom in 1894. The remains were estimated to be over 15,000 years of age and found in cave deposits in NSW on Gundungurra Country.

The identity of this jawbone confused palaeontologists for almost 50 years, until better techniques for isolating bone from the rocks were utilised. At one stage, it was thought to be a missing link between possums and kangaroos/wallabies. Image credit: Robert Broom.

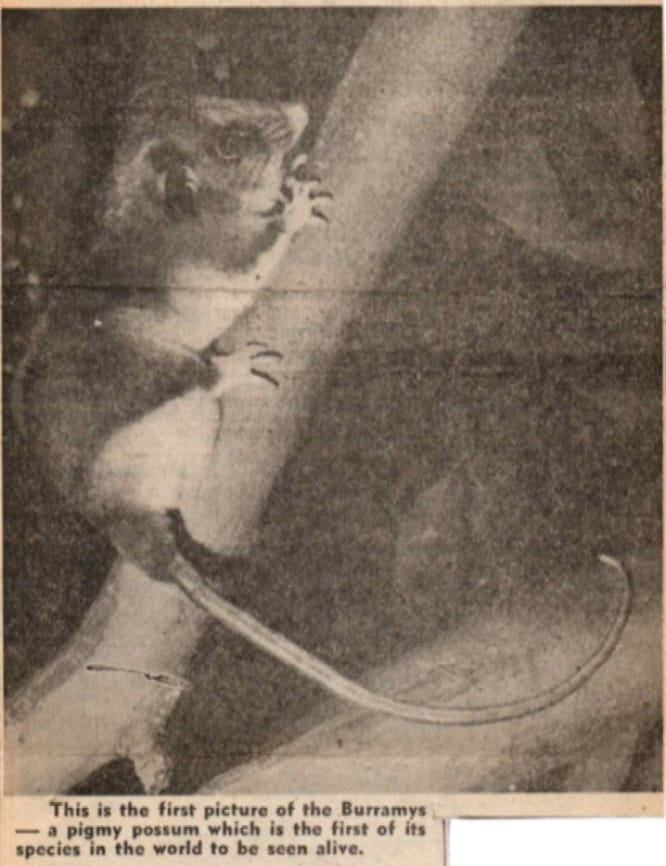

For over 70 years, the only known evidence of the Mountain Pygmy Possum was of a handful of fossil bones and teeth, until one day in August of 1966. A group of skiers on Mt Hotham discovered a “strange looking rat” in their ski-hut, that was clearly different from the other rodents. Reports vary, but some state that this strange-looking animal was “stealing the bacon from their stove”. The strange rat was captured, and affectionately named George. He was taken to Melbourne by one of the skiers who intended to give it to his 4-year-old daughter as a pet but was later confiscated to be studied for science.

Australian palaeontologist and botanist Norman Wakefield made the “EUREKA” moment whilst studying George. It was an incredible moment in Australian science, but it would take a few years until scientists found another living Mountain Pygmy Possum and could start to understand the population dynamics of this enigmatic possum species.

This is one of the few images of George that still exist, announcing the existence of a living Mountain Pygmy Possum in a 1967 newspaper clipping. Image provided by Peter Homan.

Habitat

When George was found, it was initially thought he was a hitchhiker from lower altitudes. Mountain Pygmy Possums are the only possum species in Australia that don’t live in trees. Image credit: Parks Victoria.

Behaviour and Diet

Threats to Survival and Conservation in Parks Victoria

As mentioned previously, the density of Bogong moth populations is a huge factor in successful breeding efforts for this possum. In 2017-18, more than half of all females monitored lost their litters. There are numerous overarching threats, and Parks Victoria has a tremendous legislative responsibility to look after the habitat of this possum.

One must become ChOnK if they are to survive the harsh winter, as this individual munches on the berry of a Mountain Plum Pine. Image credit: Parks Victoria

Back in 1983, the Alpine National Park was extended to include important Mountain Pygmy Possum habitat on the western slopes of Mt Higginbotham. Throughout this time, Parks Victoria and numerous other agencies have successfully managed the critical interface between their habitat and the numerous hazards that threaten their survival. To carry this out effectively, Parks Victoria must:

1) Actively monitor and reduce known populations of foxes and feral cats in this area through various control methods. The monitoring of rabbit populations is key, as they can sustain high populations of pest predators. The scat and gut contents from feral cats and foxes are routinely analysed to determine if this possum is on the menu.

Parks Victoria staff have previously used cat traps to control populations of feral cats. Feral cats are hardwired to be attracted to smelly and at times, gut wrenching scents of dead animals, but have proven difficult to catch in national parks. Image credit: Parks Victoria