Visiting the dentist or an ear, nose and throat doctor can already make patients feel uneasy, and for those who can’t wear a mask due to the nature of their procedures, the transmission of COVID-19 has become an additional concern.

Researchers from Cornell have proposed a solution in the form of a transparent helmet that prevents 99.6% of virus-containing droplets exhaled by patients from reaching the environment. The helmet provides practitioners access to the patient’s nose and mouth and is connected to a filtration pump that reverses the flow of air to prevent droplets from leaving, avoiding contamination of the clinical environment.

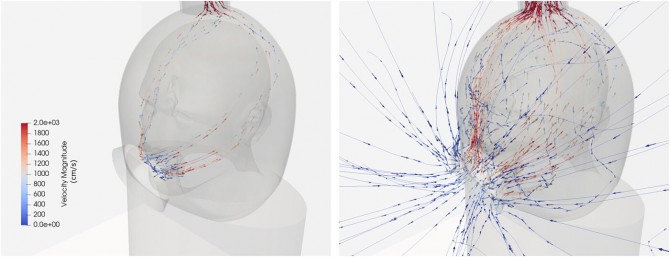

A simulation shows the flow of air from the mouth and access port toward the vacuum port.

Led by Mahdi Esmaily, assistant professor in the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, the design was published Jan. 12 in the journal Physics of Fluids.

The idea was developed during the beginning of the pandemic, when clinicians from Weill Cornell Medicine were having difficulty trying to isolate themselves from the pathogen-bearing droplets expelled by patients during certain procedures. Weill Cornell Medicine’s Dr. Anais Rameau, an assistant professor of otolaryngology, and Jonathan Lee Baker, an assistant professor of research in neuroscience in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute, contacted Esmaily for assistance in developing and running simulations of the helmet, and he quickly focused his efforts on simulating the movement of respiratory droplets.

“It turns out the ones that are most dangerous are medium size,” said Esmaily. “The reason being is that those that are very small, evaporated very quickly, and those that are large, quickly dropped to the floor, so they don’t remain airborne to transmit disease.”

The Esmaily Lab is particularly suited to run these simulations because of their background in fluid mechanics. Fred Jai, a doctoral student working with Esmaily, ran simulations that captured the airflow around the helmet and at the same time, ran simulations to predict the motion of the droplets as they exited the mouth.

“We used a one-way coupled particle simulation, which means that we simulated the airflow first, then we took the airflow information and released droplets of different sizes into the airflow field to see where they would go,” says Jai.

Aside from the helmet’s effectiveness, its simple design and low cost make it more accessible than others options for preventing virus transmission during open-mouth procedures, such as remodeling a building’s air-filtration system.

Esmaily and Jai plan to start building a prototype of the helmet using 3D printing. They’ve reached out to the Rapid Prototyping Lab, a facility in the Sibley School that is run by students and contains a variety of 3D printers, a laser cutter and computer-numerical-control router table. After they have a prototype, the team will request additional funding to study a range of flow conditions.

The research was funded the Atkinson Center for Sustainability as part of a series of rapid-response grants for COVID-19-related research.