Often museums do not know how to best enable access to their collections and exhibitions for those who are blind or have low vision (BLV).

The project aims to add ‘touch models’ to museum collections, allowing their collections of artworks, artefacts, and specimens, to be replicated providing equal engagement to those with vision impairment.

“While some initiatives for blind and partly sighted audiences do exist in museums to allow for the reproduction of collection pieces for touch, they are rare,” said Dr Reinhardt Associate Professor of Architecture, and lead researcher.

Other members of the research team are University of Sydney’s Eve Guerry and Jane Thogersen from the Chau Chak Wing Museum (CCWM), Philip Poronnik, Claudio Andres Corvalan Diaz, William Havellas, Faculty of Medicine and Health (FMH) Media Lab, Leona Holloway, Monash University, Sonali Marathe, Nextsense and Birgit Christensen, Institute for the Blind and Partially Sighted, Denmark.

“Inclusivity and accessibility for our audiences is extremely important to the Chau Chak Wing Museum,” said Dr Jane Thogersen, Academic Engagement Curatorial Team.

“Our collaboration with the School of Architecture, Design & Planning is a key example of interdisciplinarity between the museum’s Object-Based Learning (OBL) Program and academic research.”

“The touch models produced as part of this project, by staff and students, will add an important layer of deep engagement and extra sensory exploration for so many audiences, particularly those who are blind or have low vision,” continued Dr Eve Guerry, CCWM Academic Engagement Curatorial Team.

“What is really interesting about the project is the element of re-interpretation and storytelling, implicit in the thoughtful design of these models.”

Nature collections, of the type we often see in natural history museums, contain fragile objects which can only be preserved by keeping them behind glass. Further to this, there are currently no exhibition design frameworks for how to make objects, artefacts, and specimens accessible in meaningful ways and no comprehensive research or documentation as to how touch representations can be best exhibited and interacted with in museums.

In 2022, the team started exploring translations from exhibits to touch models. Here, rough scans and remodelling were used to develop tactile representations and narratives that allow blind and low vision audiences to engage with the CCWM collections.

Case Study 1: Wet Specimen, Macleay collection

The Frogfish example contains wet specimens grouped in a sealed jar (Jar of Frogfish, NHF.1150). So, a base scan of the specimen was taken to form a model, which was then reconstructed on Blender – a 3D software tool used for creating 3D-printed models.

The model was mirrored and inflated to imitate the original shape and exterior patterns. After the curing process the texture resembled that of the preserved fish. Silicon, with its durability and flexibility, was used to create multiple moulds which people could freely interact with and understand its physical characteristics.

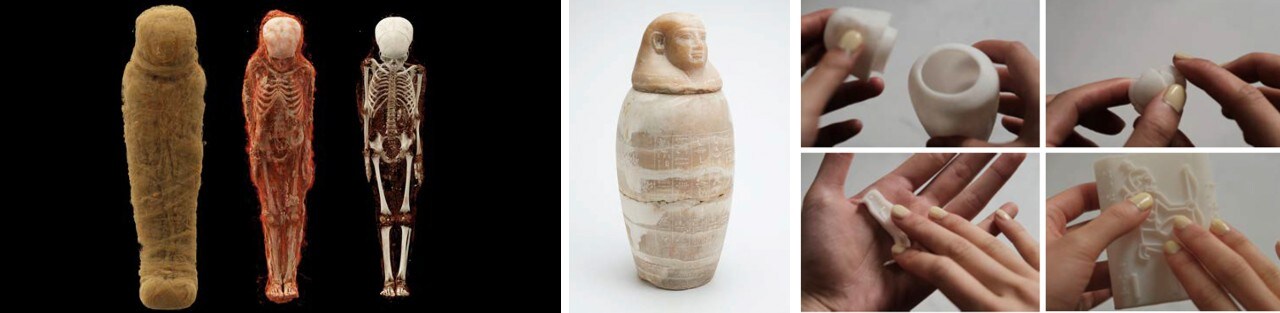

Case Study 2: Unpacking Bodies, Mummies

Museums demonstrate embalmed bodies – mummies – by opening the sarcophagus or canopic jar to reveal their contents via x-ray and are displayed visually. While this could be translated into an audio description, the canopic jar is transformed into a touch object that contains both representations of organs/objects, icons, and hieroglyphs.

But there is more.

“We are currently developing, in consultation with OBL and blind and low vision partners, touch models for natural history, and test cutting edge 3D scan and photogrammetry with the Faculty of Medicine and Health Media Lab; and scripting and 3D print methods,” said Dr Reinhardt.

“Museums increasingly scan their collections to make them accessible for a wider online audience. This is a fantastic dataset that can be used to produce touch models with the by now ubiquitous 3D printing technologies that exist in schools, libraries, and cultural institutions.”

Case Study 3: Boxfish, Macleay Collection

The Boxfish (NHF.1398) is a fragile and vulnerable sample – a mounted skin that is over 150 years old.

The FMH Media lab team produced a 3D light scan and merged the point cloud as a 3D model. The resulting data was uploaded to Sketchfab, a 3D modelling platform, for the CCWM’s digital exhibition.

In addition, a scaled replica was printed by the School of Architecture’s Design Modelling and Fabrication Lab as a high-resolution resin print. In consultation with the blind and low vision advisers, the research team developed a pattern script to highlight the fish’s typical scales with a raised profile.

“We will then run an in-depth survey that asks the blind and low vision community what they want to experience in a museum visit.

“We will build on this, review current museum trends and establish new methods and design practices for touch models,” said Dr Reinhardt.

In discussion with curators, the team will be able to identify and prepare more curated pieces that are fit for these ‘touch models’, such as diatoms, whale bones, and fragments of the moon surface.

All the workflow and knowledge gathered from this project will then be made available to museums and cultural institutions to implement – a user manual on the methods and technologies that could be adopted, along with a guideline of best practice.

“The hope being to create a new museum experience for everyone, with a tactile experience that explicitly supports BLV people,” said Dr Reinhardt.

“And ultimately this also benefits museums – allowing them to engage with a wider audience and ensure that the cultural narratives and knowledge that these objects represent is shared with everyone.”

Declaration: This research is being funded by a 2023 Alastair Swayn Foundation International Grant.