The inaugural Thinking Futures report from the Australian Psychological Society provides a snapshot of the psychological health, resilience and wellbeing of Australians.

There is a long tail on the mental health impacts that emerge in the wake of an environmental disaster.

When assessing the psychological wellbeing of those who were impacted by the 2019-20 bushfires, 12-18 months down the track, researchers found “extremely high” rates of depression, anxiety, stress and PTSD.

Separate research shows those who lost homes or businesses in the 2017 floods in Northern NSW were 6.5 times more likely to report depressive symptoms.

And a decades’ worth of data collected around the mental health of people impacted by droughts in the Murray-Darling Basin found that one additional month of extreme drought in the previous 12 months was strongly associated with a 32% increase in monthly suicide rates.

Statistics like this will, unfortunately, likely become more common as climate-related disasters increase in Australia.

While plenty of advocacy groups are working on solutions at a government and community level to stave off the environmental impacts of climate change, it is still paramount that we equip our communities with the tools and resources they need to cope with the changes.

“We can’t bury our heads in the sand and pretend that climate change isn’t happening,” says Australian Psychological Society (APS) President Dr Catriona Davis-McCabe. “It’s already here. Many communities have been devastated by its impacts. We need to turn our attention towards preparing our community for future challenges by bolstering mental resilience levels.”

Introducing the Thinking Futures report

APS’s inaugural Thinking Futures report, launched this week, marks an important step in its commitment to embedding more knowledge and resilience into everyday Australians, to help them prepare for a future in which our climate looks and feels very different.

By drawing on quantitative public and academic data, as well as in-depth interviews with 1,000 APS members and 2,000 community members, APS has created a benchmark to measure year-on-year data to help guide the work of policymakers, government and the community.

“We see this as an incredibly important first step in forming a future-fit psychology sector,” says Dr Davis-McCabe. “While this first report focuses on the intersection between mental health and climate change, we’ve also taken a broader pulse check of the psychological health of Australians and their sentiments towards the psychology sector.”

Psychologists’ climate concerns

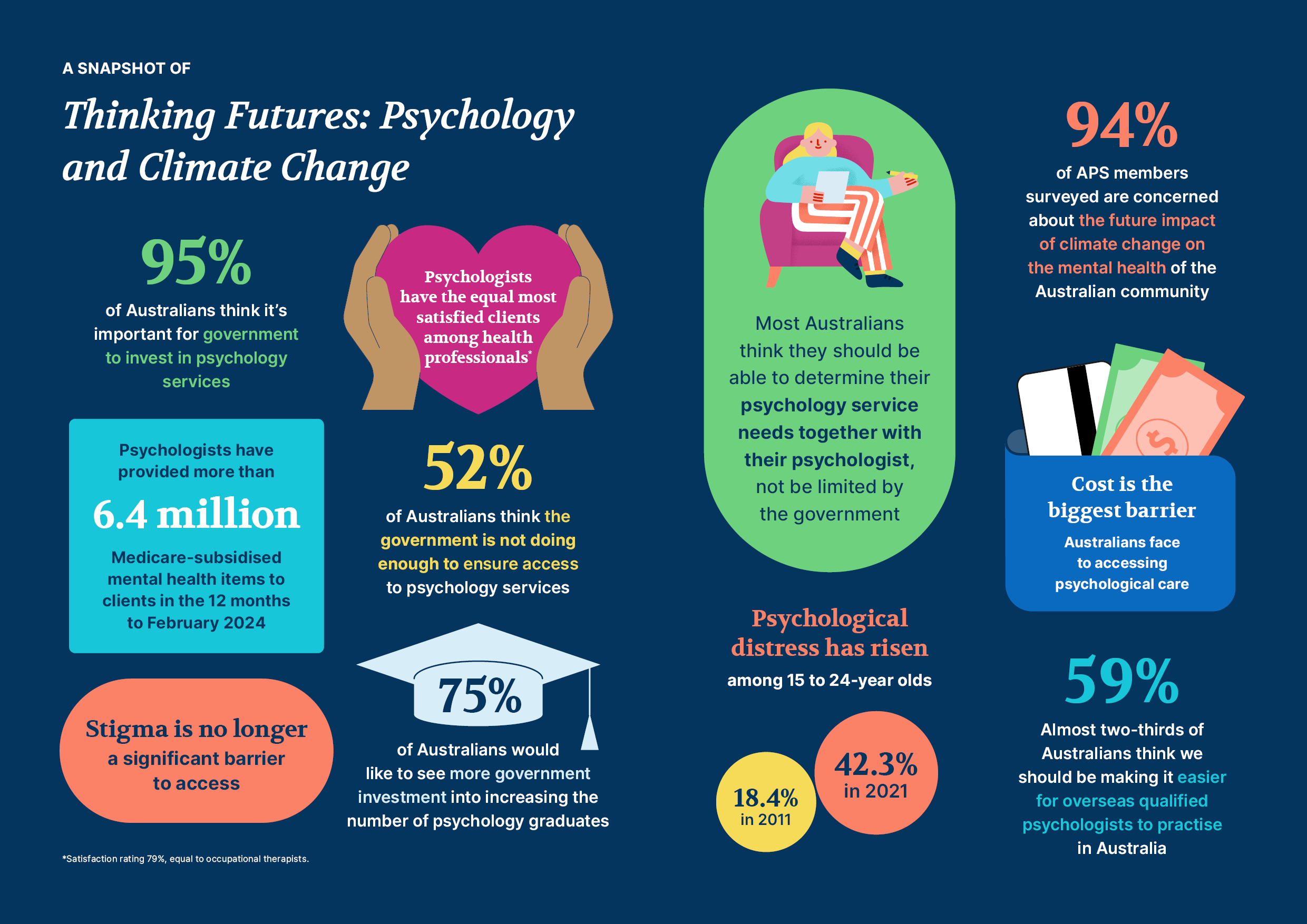

APS’s research revealed that 77% of respondents anticipate a rise in climate-related mental health issues over the next three years and 94% are concerned about the increasing toll climate change is taking on Australians’ mental health.

This sentiment is shared by the broader community, with separate research from the Climate Council showing that, since 2019, 80 per cent of Australians have experienced some form of extreme weather disaster. Of these people, 1 in 5 say the event had a “major or moderate” impact on their mental health.

Carlye Weiner MAPS, clinical psychologist, is seeing this manifest in her clients.

“I work with a lot of young people and many of them have already made the decision not to have kids because they have this sense of doom about what’s happening in the world,” she says.

At the same time, she’s also noticing an increase in clients who feel they can’t talk about their climate concerns.

“We see this spectrum of young people who are fierce advocates – they might go to protests and use their voices loudly – then there are also a lot of young people who sit in silence and internalise [their feelings and] don’t speak up about their concerns.”

This is one of the many reasons psychologists’ roles are so important; they are providing space and time for people to share their concerns.

But efforts need to extend beyond the support of individual psychologists. The Thinking Futures report found that over 70% of APS respondents wanted more government action to address the current and projected psychological implications of climate change.

“In young people in particular, government inaction is a key driver of their climate-related anxieties, so we are working closely with the government to advise where the most impactful investments of money, time and energy can be made to have the most positive impact,” says Dr Davis-McCabe.

Resilience is not just an individual trait, it’s an asset that we share in relationships,” – Dr Brenda Dobia MAPS

Tangible changes psychologists can make

Climate change is perceived as an existential threat, says Dr Brenda Dobia MAPS, psychologist and social ecologist.

“It’s raising anxiety for many of us. I think the big issue is the ongoing worry. When we think about something like post-traumatic stress… we tend to assume the stress or threat is over. But with climate change we see that threat growing.

“We’re seeing responses when people are directly affected and we’re also seeing anticipation of problems that will occur.”

The Thinking Futures report found that 92% of psychologists, psychology academics, and university students believe psychology can contribute to building resilience against the psychological impacts of climate change.

In terms of tangible steps that psychologists can take, Dr Davis-McCabe suggests:

Normalising the feelings: Assure clients that it’s common to feel overwhelmed or anxious about such a significant issue.

Defining what’s in their scope of control: Help clients identify actions they can take in their personal lives, such as reducing their carbon footprint, advocating for policy change, or getting involved in local environmental initiatives.

Encouraging clients to switch off: Suggest they limit their exposure to distressing news and imagery related to climate change, even if it’s just for a short period of time. Instead, they might benefit from spending time in nature to reconnect with aspects of the natural world that bring joy.

Cognitive restructuring: Help clients identify and challenge negative thought patterns related to climate change. Encourage them to reframe catastrophic thoughts into more realistic and manageable ones.

“It can also be useful to connect clients with others who are experiencing similar feelings to help them gain a sense of belonging and community,” says Dr Davis-McCabe.

“You may consider doing this as part of a group therapy session. This way, what originally felt like an isolating and perhaps frightening experience can be turned into a collaborative, solution-driven exercise.”

Dr Dobia agrees that a shared approach is best.

“We need to think about community resilience. How do we support each other? Resilience is not just an individual trait, it’s an asset that we share in relationships,” she says.

Hear more from Brenda, Carlye and APS CEO Dr Zena Burgess in this video on the intersection between the climate and mental health.

Bolstering the psychology profession

More broadly, APS’s research showed that instances of mental ill-health are continuing to increase.

“Our research found that among 15-24-year-olds, psychological distress has increased from 18.4% in 2011 to 42.3% in 2021,” says Dr Davis-McCabe. “The fact that mental health challenges have more than doubled in a decade – when we now have access to more research, treatments and information than we used to – is alarming.

“Climate change distress is only one of the factors driving this increase. Cost-of-living pressures, social and political polarisation, rising levels of loneliness and increased work pressures are also likely taking a toll on people’s mental health.”

We need to equip the psychology workforce with the resources and skills to respond to these emerging challenges. However, APS’s research reveals that the sector is still grappling with unprecedented demand, and cost remains the biggest barrier to access for Australians seeking psychology services.

Since the Better Access review was released, there has been a 40% increase in the most disadvantaged Australians citing cost as the reason they delayed or did not see a psychologist in 2022-23, according to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Patients Experience Survey.

“Respondents in our research were overwhelmingly in favour of reducing the cost of psychology services universally, rather than the government targeting select groups for cost relief,” says Davis-McCabe.

A trusted sector

The psychology profession will be a key enabler of a more resilient future, says Dr Davis-McCabe.

“Trust levels in the psychology profession are quite high,” she says.

APS found that 68% of Australians trust psychologists and think they deliver an important community service. This is particularly pertinent at a time where trust levels in other institutions are waning.

“Our report includes a suite of recommendations that we’ve put to the government that we think will help us build a mentally resilient Australia, including strengthening the Medicare system, increasing and extending the Medicare rebate, growing the psychology profession and addressing access issues in regional, remote and rural parts of Australia.”

Building a disaster-ready psychology workforce is an important next step for Australia, which is why APS has also called for investment to expand its Disaster Response Network, which offers volunteer psychologists free disaster response training to offer support to front-line workers in disaster impacted areas.

“We look forward to working with the Minister for Health and Aged Care, Mark Butler, and the broader government, to see these important changes through.

“I’d like to thank the thousands of APS members who volunteered their time and research to help us bring this important research to life. With strong data on our side, we can put critical change in motion.”

Download the full report here, or a summary version here. If you’d like to share some of these important statistics with your network, you can download a members’ social tile promotion pack here.