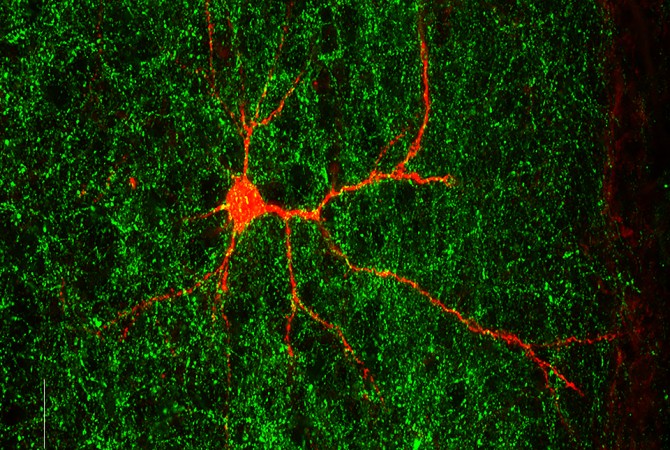

Brain connectivity is changed upon removal of an autism-associated gene. Neuron is on one side of the brain (labeled in red) and nerve endings are coming from the other side of the brain (labeled in green).

A gene linked to autism spectrum disorders plays a critical role in early brain development and may shape the formation of both normal and atypical nerve connections in the brain, according to a new study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

The study, published Nov. 28 in Neuron, employed a combination of sophisticated genetic experiments in mice and analysis of human brain imaging data to better understand why mutations in a gene called Gabrb3 are linked to a high risk of developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and a related condition called Angelman Syndrome. Both conditions involve abnormal behaviors and unusual responses to sensory stimuli, which appear to stem, at least in part, from the formation of atypical connections between neurons in the brain.

“Neuronal connections in the brain, and developmental synchronization of neuronal networks, are perturbed in individuals with autism spectrum disorders, and there are specific genes that are implicated in the pathogenesis of ASD,” said co-first author Dr. Rachel Babij, a former student in the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan Kettering Tri-Institutional MD-PhD program in the laboratory of Natalia De Marco García, an associate professor in the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The gene Gabrb3 encodes part of a critical receptor protein found in inhibitory connections in the brain, which tamp down neuronal activity to maintain order in the nervous system, like police officers directing traffic. During development, Gabrb3 also appears to help determine how brain connections form.

To figure out how Gabrb3 works, Babij and her colleagues tracked cellular signaling inside the brains of both normal animals and those lacking the gene in the early stages of their development. The preclinical experiments, which Babij performed alongside co-first author Camilo Ferrer, a postdoctoral associate in the De Marco García lab, and others, revealed that mice lacking Gabrb3 fail to form the normal network of connections between neurons in a specific brain region involved in sensory processing.

“It’s not a pervasive problem in which every single neuron will fail to contact, or inappropriately contact, their targets; but it’s actually a subset of cells that are more susceptible to this,” said De Marco García, who is the senior author on the paper.

In collaboration with Dr. Theodore Schwartz’s lab at Weill Cornell, the authors showed that the net result of Gabrb3 deletion is an increase in functional connections between the two hemispheres of the brain in the genetically modified mice, compared to those with a functional Gabrb3 gene. The genetically modified mice are also hypersensitive to touch. “Basically, what we see is that these neurons are more responsive to sensory stimuli after deletion of this gene,” De Marco García said.

The team then collaborated with the laboratory of Dr. Conor Liston at Weill Cornell to examine the role of the gene using neuroimaging data from human subjects. The investigators found a correlation between the spatial distribution of the human GABRB3 gene and atypical nerve connectivity in those with ASD. “The lower the expression of GABRB3 in specific brain regions, the more atypical nerve connections these regions were likely to contain,” said De Marco García said.

While cautioning that it is impossible to draw direct parallels between the preclinical and human data, De Marco García suggests that both analyses point to a model of neurologic disorders in which alterations in genes such as GABRB3 could drive specific changes in neuronal connection patterns, which in turn lead to abnormal behaviors. Interactions between different genes, each with slightly different effects, could yield substantially different outcomes.

Babij concurs. “What makes one person develop schizophrenia while another person develops ASD, when both have some element of inhibitory neuron dysfunction? I think something about the specific subtypes of neurons affected and the mutations impacting them could play into how people develop these different diseases,” she said.

Many Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and scientists maintain relationships and collaborate with external organizations to foster scientific innovation and provide expert guidance. The institution makes these disclosures public to ensure transparency. For this information, see profiles for Dr. Liston and Dr. Schwartz.

Alan Dove is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.