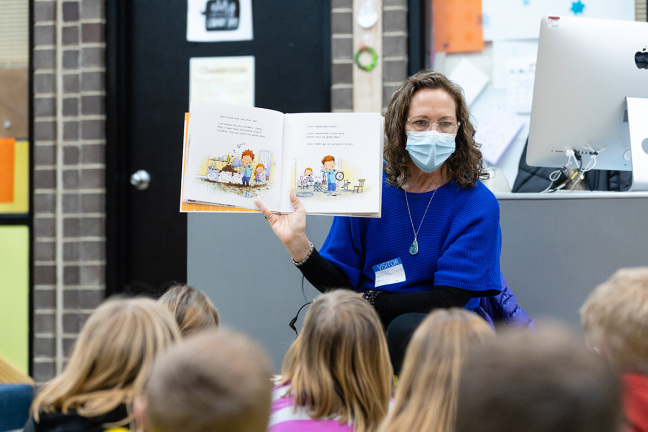

Emily Hayden, associate professor of education at Iowa State University, reads to a third grade classroom at United Community Elementary School, spring 2021. Larger image. Ryan Riley/Iowa State University.

AMES, IA — “What’s your name?” This question percolates into every-day conversations, whether chatting with a neighbor or meeting a new coworker. But Emily Hayden, associate professor of education at Iowa State University, wants to know: “What’s the story behind your name?”

“There are a lot of interesting facets to what your name says about you and who you are in a certain place,” she explains.

Hayden is one of the authors of Her Chinese Name Means Beautiful: Culture, Care and Naming Practices, a working paper that reveals nuanced and complex linguistic, cultural, and pragmatic considerations Chinese Americans take into account when naming children. The researchers wrote the paper for elementary school teachers and included book and activity recommendations to help build inclusive classrooms, all while meeting state education standards.

But they emphasized that learning how to pronounce someone’s name or showing interest in how a name is connected to culture and family history is a way to demonstrate care in the greater community, as well.

The Study

To explore Chinese American naming practices, the research team analyzed phone interviews with more than a dozen parents who grew up in Mainland China and moved to the U.S. for school or work. Participants were asked to share the stories behind their own Chinese and English names, as well as the decisions that went into naming their children who were enrolled in U.S. schools or colleges at the time of the interviews.

The Findings

All but one of the participants in the study gave their children Chinese names in addition to English names. Many of the parents said the Chinese names were a way to connect their children to their cultural heritage while the English names helped them align with mainstream culture in the U.S. Names were used on different occasions for different purposes.

“Some parents said there was no reason to use Chinese names in the U.S. because their kids are American, but when they go back to China and are surrounded by family, they’ll use their Chinese names,” Hayden explained.

Several parents said they chose Chinese names for their children based on traditional naming practices, like using birth times to determine whether their newborns lacked one of the five elements (e.g., water, fire) identified in Taoist philosophy. They then chose names with specific Mandarin characters that would address the shortage.

Others selected Chinese names with certain characters to indicate their child’s position in the family (e.g., older son, younger daughter).

When choosing English names for their children, parents drew from Western pop culture (e.g., TV characters) or the Bible, or selected names that were phonetically similar to their children’s Chinese names. Often on legal documents, like passports and birth certificates, parents designated English names as the first names and Chinese names as middle names.

“This is an example of the ‘messy boundaries,'” Hayden added.

Classroom Application

In the working paper, the researchers shared how studying the origins of names can lay the foundation for higher level writing and word comprehension.

“For example, strokes on the Mandarin characters have different sounds or syllables. That could connect naturally to understanding syllable patterns in English as kids move up grade levels,” Hayden said, giving the example of -ology, which means the study of something (e.g., biology is the study of life, geology is the study of Earth).

But the researchers also emphasized that learning more about naming practices is a simple yet meaningful way teachers can foster inclusive classrooms.

“Once teachers have some background on naming practices, they could ask all of their students to interview family members to find out if there’s any special meaning behind their name and then have the students present their findings,” Hayden said.

She said this type of project helps students build listening, thinking and presenting skills.

“Even if there isn’t a big story behind your name, you can look up what a name means and whether it’s a piece of your identity that you want to take on,” Hayden added.

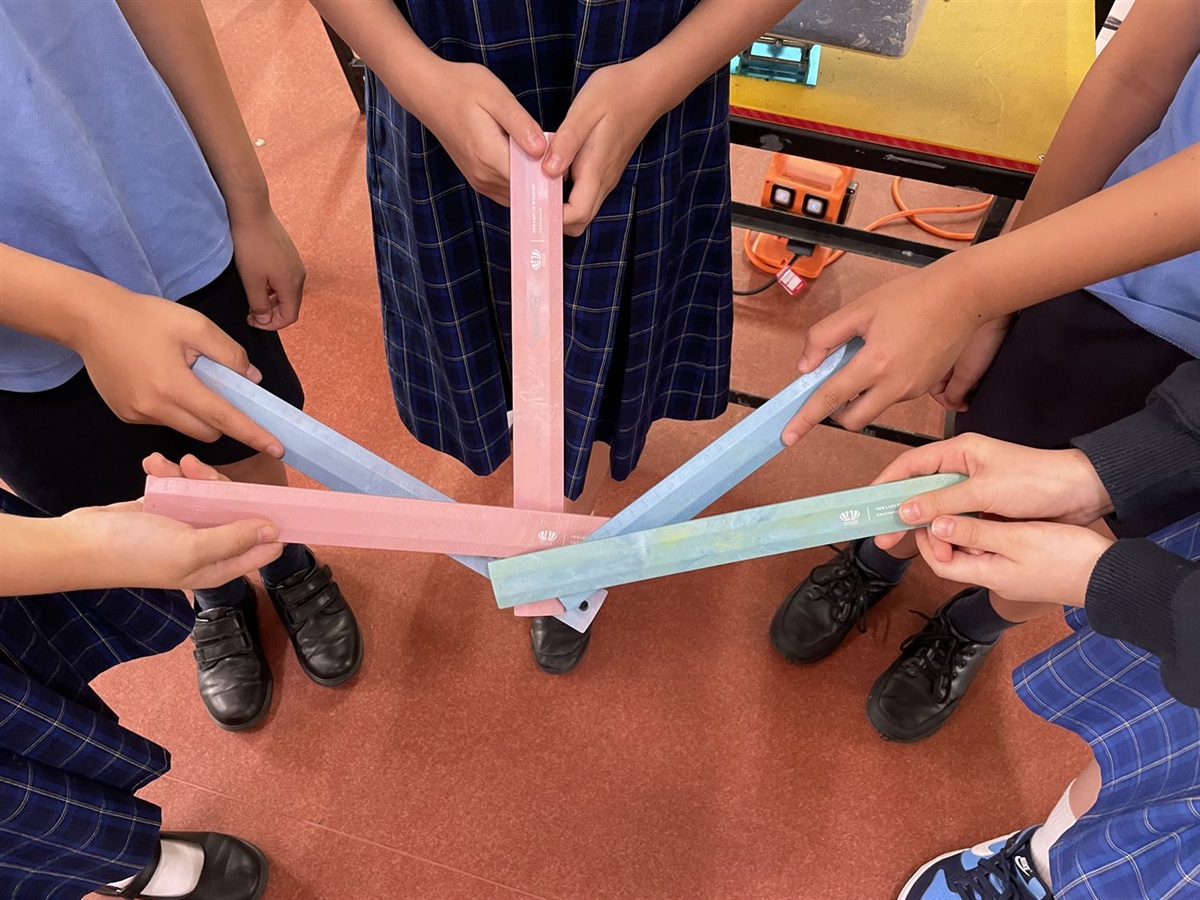

The researchers also suggested teachers could invite students to make digital posters representing their formal/school name and informal/home name, and then combine all of the students’ posters into a unified collage or quilt to remind students that their families are all unique but part of the same community.

Since COVID-19 was first reported in China, people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent have experienced increased verbal and physical attacks in the U.S. The researchers said fostering an inclusive environment can start with the humble practice of learning and respecting names.

“It’s really important to introduce kids at a young age to the idea that being different is OK; different is interesting and makes us all richer,” Hayden said.