Heading into the state election, neither of the major parties has a policy to address increasing congestion on transmission lines joining wind and solar farms to the electricity grid.

Of all the states, NSW has the highest percentage of electricity generated from coal – 80%. Although the state election is imminent and a key issue – according to public opinion polls – is climate and energy policy, NSW has neither a renewable energy target nor policies to drive a rapid transition.

Science, ethics and electrical engineering can guide the development of energy policy. Science informs us that burning fossil fuels is the major contributor to global climate change and that urgent action is needed to substitute renewable energy and energy efficiency for fossil fuels, thus avoiding irreversible changes that would make large parts of our planet uninhabitable.

Ethics tells us that it is wrong to leave climate mitigation to future generations.

Electrical engineering, including computer simulation modelling, demonstrates that it’s possible to operate the large-scale electricity system reliably on 100% renewable energy and that such a system would be no more expensive that a new fossil-fuelled system. Simulations that balance actual renewable energy supply with actual demand each hour over periods of one or more years have been performed by research groups at UNSW, ANU, Sydney University and the Australian Energy Market Operator.

These simulations show that reliability can be achieved by a system powered predominantly by variable wind and solar photovoltaics (PV) together with a relatively small amount of storage in the form of pumped hydro and/or concentrated solar thermal with thermal storage and/or gas turbines burning renewable fuels, supplemented by batteries. Baseload power stations, such as coal and nuclear that can operate 24/7, are unnecessary.

NSW Labor has committed to introducing reverse auctions if it wins government. These have been very successful in driving installations of wind and solar farms, and driving down their cost, in the ACT’s renewable electricity program. Reverse auctions have also recently been introduced in Victoria and Queensland. With the low and declining contract prices for wind and solar farms, compared with the wholesale price of electricity, reverse auctions are no longer a subsidy, but rather a means of providing greater certainty for investors.

‘The next NSW government could follow the South Australian government’s lead by providing grants to investigate the feasibility of specific off-river pumped hydro project proposals and to subsidise a concentrated solar thermal power station with thermal storage and a large battery.’

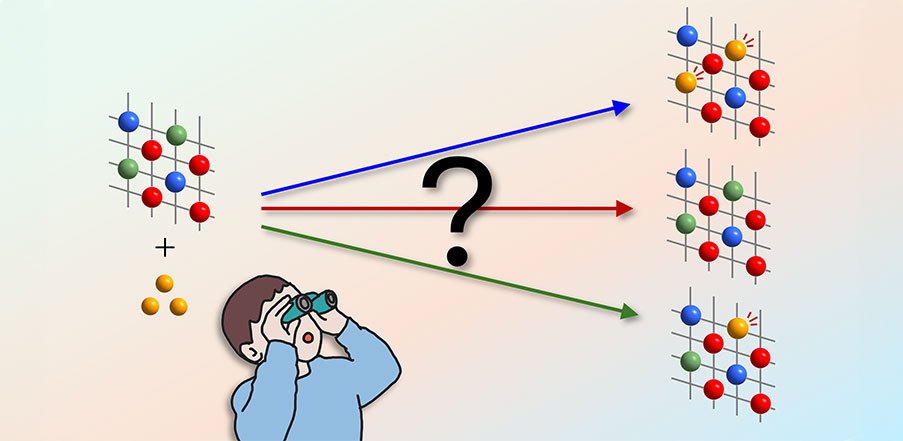

Neither of the major parties in NSW has a policy to address a problem that’s beginning to impede the growth of large-scale renewable electricity, namely increasing congestion on transmission lines joining new wind and solar farms to the main electricity grid. Wind and solar farms can be planned and built in two to three years, but transmission lines take much longer.

For example, a project is under development for a huge Renewable Energy Zone combining wind, solar and pumped hydro storage near Walcha in the Northern Tablelands. For this project to reach full planned capacity, a major transmission link is needed between the Northern Tablelands and the Hunter Valley.

Assisted by Queensland’s reverse auction policy, more electricity could be generated from solar farms currently planned and under construction there than is needed in that state. To take full advantage of that growth, the transmission link between Queensland and NSW should be upgraded.

As well as reverse auctions and new and upgraded key transmission links, the other principal policy need is specific incentives for energy storage, which is still quite expensive. In the absence of policies from the federal government, the next NSW government could follow the South Australian government’s lead by providing grants to investigate the feasibility of specific off-river pumped hydro project proposals and to subsidise a concentrated solar thermal power station with thermal storage and a large battery.

The focus here is on transitioning electricity, because a renewable energy future will be predominantly an electrical future. Most industrial and residential heat and most transport will become electrical, because that’s more efficient and cheaper. The exceptions – air and sea transport – still need further research and development to reduce the cost of hydrogen produced by using renewable electricity to split water.

The focus is also on policies for large-scale systems, because small-scale systems are growing rapidly, driven by economics and facing few barriers. Very soon, the only assistance they will need from government is incentives for batteries coupled to rooftop solar systems.

A 100% renewable energy future is technically feasible for NSW and, with the temporary exception of air and sea transport, affordable.

Dr Mark Diesendorf is an Honorary Associate Professor in the UNSW School of Humanities & Languages.