Researchers at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health helped launch North America’s first Black food sovereignty program – an effort to address food insecurity by creating a Black-run food pipeline from field to table.

The Toronto Black Food Sovereignty Plan is the result of a partnership between the City of Toronto’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism Unit (CABR) and the Afri-Can FoodBasket, a community-based non-profit that advocates for food justice and food sovereignty. Toronto City Council unanimously approved the plan last fall.

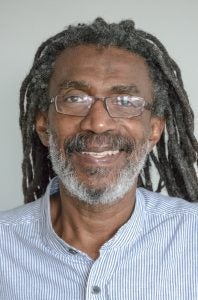

“It’s well established that there’s a chronic issue with food insecurity among Black communities in Toronto, and we think the standard approach in dealing with it won’t take us far,” says Winston Husbands, an associate professor at Dalla Lana who was part of the working group behind the plan. “We want to step outside the normal way we think about food insecurity and talk about food sovereignty, which means Black communities have some degree of control that ensures much more access to food.”

Winston Husbands

Winston Husbands

More than a quarter of Black households in Toronto are food insecure, including about 300,000 children. Research shows that Black families are three-and-a-half times more likely than white households to be food insecure – a statistics that calls for community-led solutions, Husbands says.

The plan calls for access to growing space and infrastructure, Black-led food hubs, and culturally rooted community health and nutrition programs. City agencies will provide resources such as land and water for urban gardens and education in creating sustainable food systems and minimizing waste.

The origins of the plan date to the mid-90s, when the Afri-Can FoodBasket began building capacity among individuals and neighbourhoods across the city to grow their own food. The group’s efforts led to more than 100 new gardens; a composting program; food animation workshops; seed saving; the Ujamaa Urban Farm, with sites in Toronto and Brampton; the Black farmers incubator training program; and Cultivating Youth Leadership, a youth community food security program.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity worsened in the city’s Black communities. The FoodBasket responded with Black Food Toronto, a traditional food bank that helped to meet immediate needs for access to culturally appropriate food. But Husbands and others, including Imara Rolston, an assistant professor at Dalla Lana, were already thinking about longer-term solutions.

“There’s the idea of recognizing that access to food is a human right,” says Husbands, a former research director of the Daily Bread Food Bank. “But then we need programs and policies to make it really effective.”

The plan also differs from traditional food security efforts because it addresses racism as a major cause of food insecurity in Black communities. Without this understanding, traditional efforts privilege certain groups and undermine the health and wellbeing of others, Husbands says. He draws an analogy from his work in HIV research: “You might say everyone should get tested for HIV without understanding why different segments of the population are not getting tested. Then some will lag behind, and you end up thinking that people work against their own interest.”

Considering anti-Black racism as part of a food sovereignty plan means asking questions like why there are so few Black farmers in Ontario, or why many food stores in Black neighborhoods are not owned by community members, Husbands says – and investing resources to address these gaps.

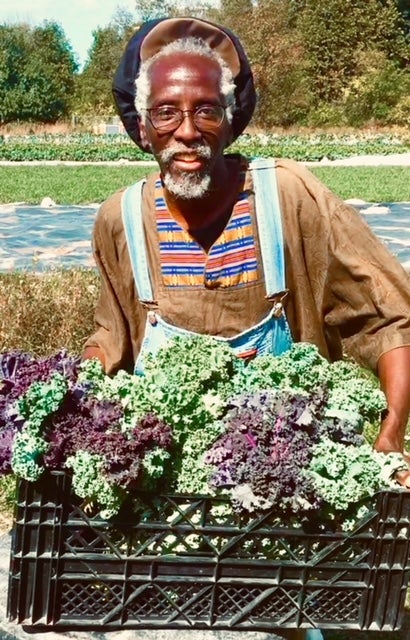

The food sovereignty plan came together under the leadership of a long-time Black food activist Anan Lololi, executive director of the FoodBasket, who spearheaded the plan with CABR’s Melana Roberts.

Anan Lololi

Anan Lololi

“We want to work with nature, value urban farmers and nutritionists. We want to make sure we realize the sacredness of food,” Lololi says. “Food is a business but really it’s a human right. We want to look at it appropriately.”

Lololi says he was surprised at how quickly the plan was adopted by council – a nod, perhaps, to the increased need to create community resiliency in the face of disruptions like COVID-19. During the pandemic, Black Food Toronto says it has distributed one million pounds of food with support from CABR, Community Food Centres Canada, Network for the Advancement of Black Communities and the public. Vegetables have also come from Ujamaa Farm and the Backyard Urban Farm Company, but without the kind of infrastructure that such a complex operation requires.

“We’re doing this with blood, sweat and tears because we don’t have the resources to do it, not even a warehouse,” Lololi says. “The next steps from the Working Group are to mobilize our knowledge base. Bring food policy folks, those who know about farming and gardening, the activists, academics, nutritionists and food businesses to collectively determine the future of food sovereignty in Canada.”