- New data puts Northern Italy on the same climate trajectory as parts of Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa, which recently faced its worst drought;

- Cutting-edge satellite imagery demonstrates how communities are exposed to a double whammy of floods and droughts;

- Real life stories of people coping with these two extremes, as WaterAid warns that failure to act on climate adaptation at COP28 will have catastrophic consequences

Exclusive new research today from WaterAid reveals that millions of people around the world living in poverty, have been experiencing a ‘climate hazard flip’ since the turn of the century. This comes at a pivotal moment, as world leaders prepare to meet in Dubai for COP28 in two weeks’ time.

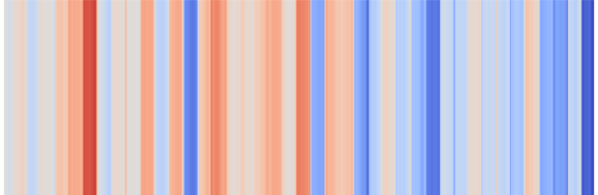

Accompanied by powerful satellite imagery, the analysis of climate data released by WaterAid and Cardiff and Bristol Universities finds that under a ‘whiplash’ of extreme climate pressures, areas that used to experience frequent droughts are now more prone to frequent flooding, while other regions historically prone to flooding now endure more frequent droughts – having a devastating effect on communities in these regions.

Over the last two decades, areas in Pakistan (seen in the images above), Burkina Faso and Northern Ghana – normally associated with hotter, drier conditions – have flipped to become increasingly wetter and flood-prone.

By contrast, the southern Shabelle region of Ethiopia, which between 1980-2000 experienced numerous periods of flooding, now shows a shift towards prolonged and severe drought. The drier Shabelle River – a major water source for Somalia – recently experienced the worst of the drought conditions in the Horn of Africa but ended with a major flood in April this year.

It is a phenomenon mirrored in Northern Italy where the data shows the number of intense dry spells experienced by both countries has more than doubled since 2000. But these are punctuated by risks of extreme flooding, as the Lombardy floods of May and July this year illustrate.

The innovative research examined the frequency and magnitude of flooding and drought hazards over the last 41 years in locations across six countries where WaterAid works: Pakistan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Mozambique, adding Italy for a European comparison to address the fact that the impacts of climate change do not discriminate by region.

Communities exposed to these extremes are often ill-equipped to deal with them. WaterAid warns that failure to act on climate adaptation at COP28 could condemn people in the worst affected areas to entrenched poverty, displacement, disease and potentially even conflict, as issues leading to water and food scarcity are made worse by catastrophic and changeable climatic extremes.

Tom Muller, WaterAid Australia’s Chief Executive, said:

“The climate crisis is a water crisis and, as our research today shows, our climate has become increasingly unpredictable with devastating consequences.

“From drought-stricken farmlands to flood-ravaged settlements, communities in Pakistan, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Ethiopia are all experiencing alarming climate whiplash effects; Uganda is experiencing ever more catastrophic flooding and Mozambique a chaotic mix of both extremes.

“While we will all pay a price for global water stress, it’s those living on the frontline of the climate crisis who are paying for it now – their lives hanging in the balance.

“COP28 is only two weeks away and it cannot be another summit where the climate adaptation can is kicked down the road. Our leaders must recognise the urgency and prioritise investment into robust and resilient water systems now.”

For communities living on the front line of these ‘climate hazard flips’, the consequences are devastating – wiping out crops and livelihoods, damaging often-fragile water supply infrastructure, disrupting water supply services, and exposing people to disease and death.

In 2022, the village of Bachal Bheel in the Badin region of southeast Pakistan was devastated by catastrophic flooding that engulfed two-thirds of the country. Local resident and widow, Soni Bheel recalls a childhood when local agriculture prospered with an adequate balance between heat and water supplies, allowing villagers to enjoy “robust health”.

Now Soni, 83 years old, says, the situation is very different:

“Our village was washed away in the flood, but it taught us a vital lesson: we must build our houses on higher ground to protect them from future floods. We’re now elevating our homes with a two-foot-high platform.”

The floods also pollute drinking water sources – Momal Abdul Qayyum, 44, from nearby Tando Bago said:

“Each drop of water is valued like ghee (pricey clarified butter), treated as a precious and expensive resource.”

In Uganda, the data shows that Mbale, an Eastern region in the shadow of Mount Elgon, is also showing a significant tendency towards much wetter conditions, as demonstrated by unprecedented flooding over the last three years. For retired primary school teacher, Okecho Opondo, 70, the change in weather patterns is causing huge problems.

“We are in total confusion. The months that used to be rainy are now dry. When the rains come, they can be short yet heavy, leading to floods. On other occasions the rainy periods are too long, leading to destruction of infrastructure and crop failure. And then the dry periods can be very long, further leading to crop failure and hunger.”

Rose, a 28-year-old mother of three explains the impact of flooding on local water supplies:

“In our village we have two boreholes. During the rainy seasons the first borehole is always covered in mud that comes with water from upstream, this further affects the water quality. Sometimes people get sick after drinking the water from the boreholes, there was a time when health officials advised us to stop drinking water from the two boreholes for six months.”

Two measures the local community have tried to mitigate the climate uncertainty are to plant hedges around their crops to help prevent soil erosion and to move latrines well away from potential flood zones. One person spoke of planting bamboo forests on the slopes of nearby Mount Elgon to try to prevent landslides.

Meanwhile in Mozambique, in the highly urbanised areas around the capital of Maputo, the data shows the situation as highly variable, characterised by prolonged drought periods punctuated by floods.

14-year-old student, Kiequer, whose parents now work in South Africa, was forced to relocate to a resettlement centre with his aunt after his house was damaged by the floods. Now they face the opposite problem of water shortages, with long queues at the well or expensive commercial standpipe water they can’t afford.

Kiequer, 14, spoke of the long-term impact:

“The floods really affected my education. My academic knowledge went with the water. I was traumatised by that February rain. When the sky gets cloudy, I always get scared. I don’t think that day of the floods will ever leave my imagination.”

Co-lead researcher, Professor Michael Singer of the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Cardiff University, warned these climatic phenomena are not just confined to these countries:

“Most dramatically, we found that many locations are undergoing major shifts in the prevailing climate. Specifically, many of our study sites have experienced a hazard flip from being drought-prone to flood-prone or vice versa.

“Although the scope of this study was limited to a handful of countries and specific locations within them, we believe the hazard flip and, more generally, changes to flood and drought hazard frequency and magnitude are something most places on the planet will have to address.”

Co-lead researcher Prof Katerina Michaelides, Professor of Dryland Hydrology at the University of Bristol Cabot Institute for the Environment, added:

“We have come to understand that climate change will not lead to a monolithic change to climatic hazards, despite globally increasing temperatures. Instead, the hazard profile for any region is likely to change in unpredictable ways. These factors must be considered to support climate adaptation for the lives and livelihoods of humans across the globe.”

From flood protection to drought resistance measures – adaptation solutions exist, but not enough is being done to prepare for this future. Scaling up and optimising water-related investments in low and middle-income countries will not only save lives, it will boost economic prosperity – with analysis suggesting it can deliver at least $500 billion a year in economic value.

WaterAid is calling on world leaders at COP28 this year to prioritise clean water, decent sanitation and good hygiene as a key component to climate adaptation programmes as well as rapidly scale up in investment in water security in low- and middle-income countries:

- High income countries must more than double their public finance for adaptation from 2019 levels by 2025 and match climate funding amounts to mitigation funding.

- High income country governments, financing institutions and the private sector should provide at least £500m towards a total of £5-10bn needed for water security over the next 4 years.

- In the UK, following a series of rowbacks on climate commitments, WaterAid is calling on Rishi Sunak to show leadership at COP28 – including the UK government investing one third of the UK’s international climate finance budget towards locally led adaptation projects that will bring a year-round supply of clean water to those most in need – and to influence other global governments to make similar commitments.

Tom Muller concludes that this is a clarion call to world leaders to act now or risk the lives of millions:

“For the world’s most vulnerable, this is a matter of life or death. We cannot let climate change wash away peoples’ futures.”