How the Charles Perkins Centre’s unexpected collaborations are fighting chronic diseases

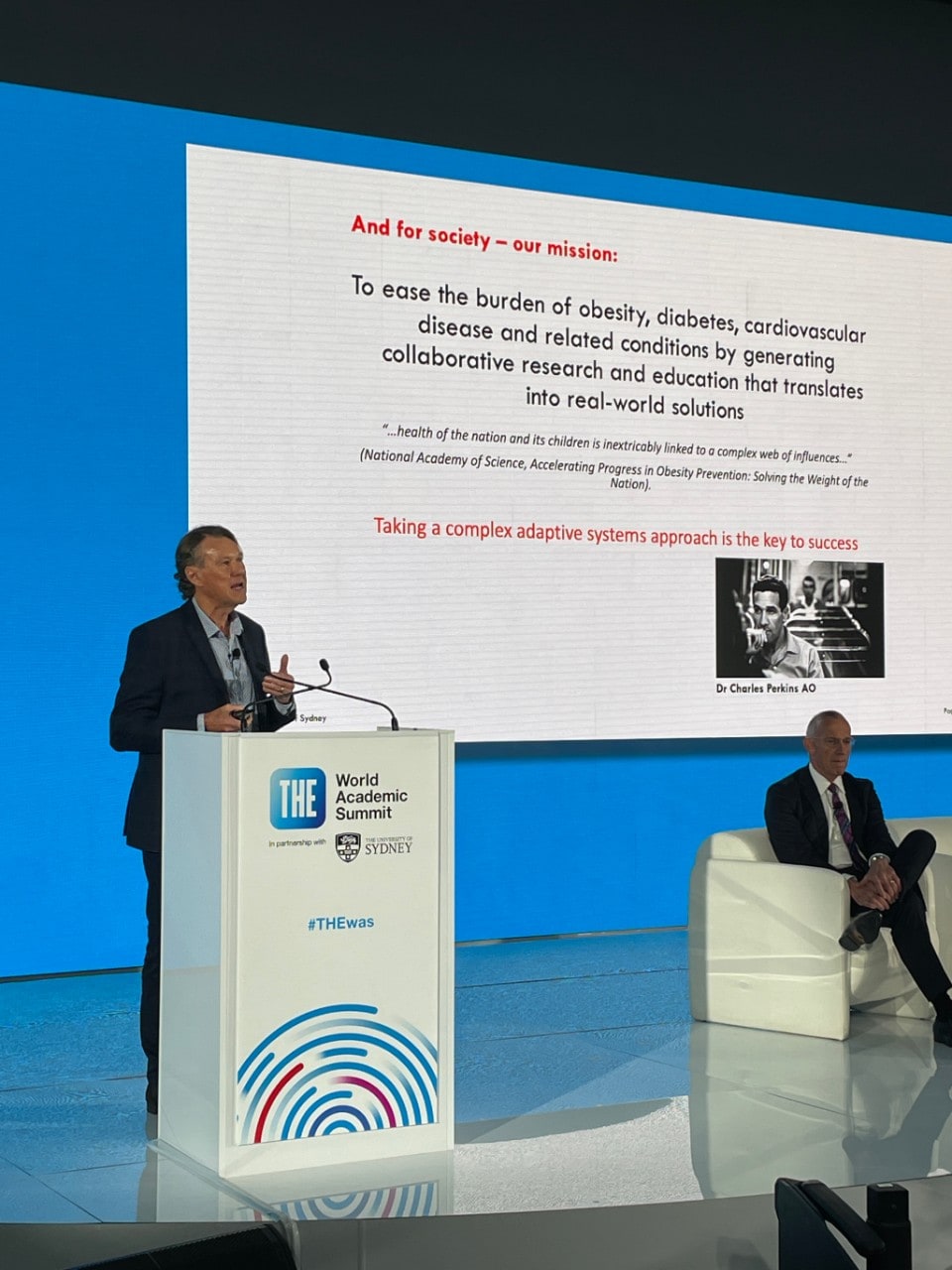

Keynote address delivered by Professor Stephen Simpson, Academic Director of the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre, followed by a discussion moderated by Times Higher Education Chief Global Affairs Officer Phil Baty with:

- Professor Stephen Simpson, Academic Director, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney

- Professor Michael Spence, President and Provost, University College London

Mr Baty introduced the Charles Perkins Centre as an outstanding example of interdisciplinarity, with today’s session focused on how we instil this in universities.

Professor Simpson opened with a photo of himself and Professor Spence – a former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney – auctioning a Picasso artwork donation that began his journey as inaugural academic director of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre.

“This was the first of the University’s attempts to bring itself together around a set of complex societal issues that could take advantage of the University’s depth and expertise,” said Professor Simpson.

The Centre would become a prototype for the University – much more than a $400m building – it was a strategy that brought academics together with a mission to ease the burden of chronic disease.

Professor Simpson took a complex adaptive systems approach. If the model was set up correctly, he knew key themes and breakthroughs would emerge – often unexpectedly.

“There was a single overarching mission, but who was I to tell people in advance about whether what they thought they wanted to do was relevant to that mission? I didn’t want to pre-empt what people should be doing… We needed to foster that entrepreneurial spirit,” he said.

At the beginning he spent considerable time encouraging people to come forward with their dream project, and provided small seed funding, workshopped ideas and collaborations and then let it go.

The Centre tracked progress via shared publications and funding. The data spoke for itself – with the emergence of distinctive areas of strength.

As the Centre celebrated its 10th birthday, Professor Simpson highlighted novel partnerships and successes including the Qantas collaboration on jetlag, the Cardiovascular Initiative and ACvA, The Obesity Collective and the Judy Harris Writer in Residence Fellowship.

In discussion time, Professor Spence spoke of the shared ambition of Syndey and University College London to tackle grand challenges via multidisciplinary research.

He said the key was for institutions to keep celebrating disciplinary excellence but at the same time celebrate and reward this kind of multidisciplinary solutions-focused work.

To be successful, Professor Spence suggested the big question needed to capture the imagination of the academic community at that point in time, touch the enthusiasm of many academics, have funding opportunities and a charismatic leader that brings people together.

Leadership reflections moderated by Professor Robyn Ward, Executive Dean and Pro Vice-Chancellor, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney. In discussion with:

- Erik Renström, Vice-Chancellor, Lund University, Sweden

- Nick Fowler, Chief Academic Officer, Elsevier

- Michael Bowen, Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, Kinoxis Therapeutics

- Krishan Thiru, Country Medical Director, Pfizer Australia

This session examined how partnerships with industry can ensure that the research output of universities has real-world impact, both regionally and internationally.

Professor Ward discussed the University’s 2032 strategy, a key tenet of which is increased collaboration between academia and industry. A central piece of this strategy is the Sydney Biomedical Accelerator, which will physically connect Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and the University for the first time.

“The magic in this Accelerator is that ‘accelerator’ word, where we bring industry in as a third party in this partnership and really ensure that we are accelerating those research discoveries into clinical care.”

Associate Professor Bowen said that interdisciplinary work both within and beyond academia will be key to getting academics’ ideas heard by industry.

“One of the most important things Kinoxis has done is connect knowledge and expertise in the core technology held by the University with expertise from outside of academia across a really wide range of areas spanning drug development, clinical trials, patent law or business marketing.

“If we only had one of these areas of expertise, we wouldn’t have achieved anything. It’s only in bringing all this together that we’ve been able to position ourselves to have a real shot at impact.”

Bowen added that incentives will be needed to encourage academics to seek out industry partners and high-impact publications where their work will be noticed.

Dr Fowler agreed, noting that Elsevier had found research publications co-authored with corporate partners had citation impact scores 62 percent higher than papers without industry input.

Fowler also mentioned that universities are increasingly seeking to partner with their local industries, to drive and build development in their own neighbourhoods.

Professor Renström’s example of local development around the University of Lund underscored Fowler’s point. His university has strong relationships with regional technology heavyweights including Ericsson, Nokia and Axis Communications, which has help secure support for research and development.

Dr Thiru said that fostering these kinds of connections early in a research project’s lifespan can find what industry can offer.

“We’re not just a source of funds, but another source of expertise. Industry has the power to take research from the bench to bedsides all around the world.”

The panel concluded by agreeing that governments have the power to shape and support collaboration, by identifying national strengths and priorities and by incentivising partnerships that build local capabilities.

Keynote discussion moderated by Kirsten Andrews, Vice-President of External Engagement, University of Sydney, with:

- Julie Cairney, Pro Vice-Chancellor of Research, Enterprise and Engagement, University of Sydney

- Kim Dong-One, President, Korea University

- Ari Kuncoro, Rector, Universitas Indonesia

- Ben Nelson, Founder and CEO, Minerva Project, Founder and Chancellor, Minerva University

- Steven Worrall, Regional Managing Director (ANZ), Microsoft

There was standing room only for the session, where panellists discussed the challenges and opportunities universities face when it comes to partnering.

Ben Nelson, Founder and CEO, Minerva Project, Founder and Chancellor, Minerva University, kicked off the conversation by talking about the common traits successful starts ups share, which is “the core ideas that animate them” and how they are using a similar approach in education.

“We provide a set of cognitive tools that our students master, not just by knowing them, but by knowing how to apply them across very diverse types of opportunities,” he said.

Professor Kuncoro, Rector, Universitas Indonesia, talked about the pressing need to improve the adaptive skills of students and teach them how to adapt when they don’t know or understand the external environment. He added that many academics are also not trained specifically on how to talk to industry partners.

“The problem is not easy. I like to borrow the title from the Star Trek movie – First Contact – who will be the first contact?”

Professor Dong-One, President, Korea University, spoke about the strong partnerships that the University has with Samsung, where they have a department dedicated to research and development of next-generation technologies and where students receive their education coupled with hands-on experience and a guaranteed job after they graduate. He says this has helped to bridge the gap between university and industry.

“Nowadays the crisis of university is the distance between university and the real world, this is one way to rectify that problem.”

The next phase for higher education

Keynote address by Anant Agarwal, Founder and CEO, edX. Moderated by John Gill, Editor, Times Higher Education.

Professor Anant Agarwal focused his address on the incoming artificial intelligence (AI) revolution that he said will be as big as, or eclipse, the digital revolution – telling the crowded atrium that everyone needs to be prepared for change.

Citing a recent survey of 800 CEOs, who were asked what is the most important skill people need to learn, Professor Agarwal said the most common response was a new discipline called prompt engineering.

Prompt engineering is the process of inputting instructions into a computer program, like ChatGPT, using words, so it can understand what you want and provide the right answers or responses.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, be it a professor or a CEO or a frontline worker, you need to be getting abreast of AI learning prompting,” Professor Agarwal said.

“Really begin to practise and play with prompt engineering – that would be my first piece of advice.

“Just as you have a Google search window open on your desktop, everybody should have a ChatGPT window.”

Professor Agarwal suggested universities need to pay close attention to and adopt AI because it will allow widespread personalisation of education, enabling students to have learning tailored to them.

“As an example, at edX we just launched a learning tutor in many of our courses, soon to be available in all courses, where learners can interact with AI, we can serve as a personal coach, where it remembers the conversation and can help the learner learn,” he said.