The first tests of a drill designed to extract an Antarctic ice core with a one million year climate archive, are underway at the Australian Antarctic Division.

The Million Year Ice Core (MYIC) Project drill, which will drill to a depth approaching 3000 metres, in temperatures as low as -55°C, is being built by Antarctic Division engineers and instrument technicians, using drawings provided by American colleagues, based on a Danish design.

Traverse Capability Project Manager, Tim Lyons, said the team has tweaked the design to suit Australian scientists’ needs and the likely operating conditions at the Little Dome C drill site.

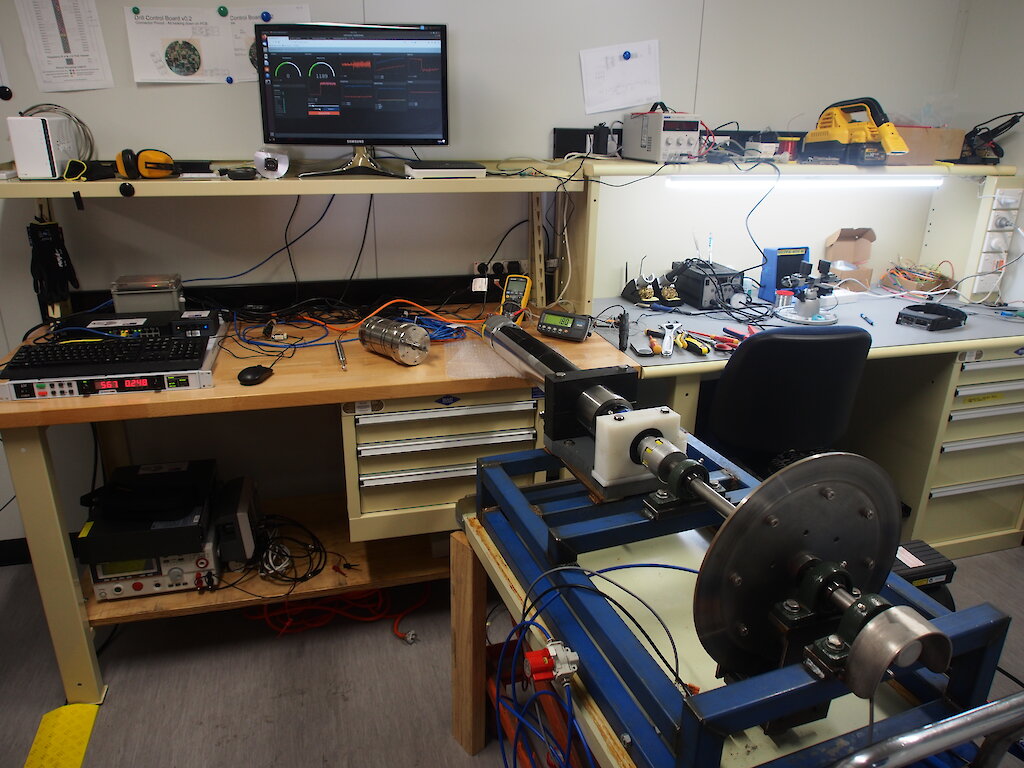

“The main part of the deep ice core drill system is the drill sonde, which consists of the spinning drill head that cuts into the ice, a three metre core barrel to collect the cores, a motor, gearbox and electronics package to drive and control the drill, and an anti-torque section that stops everything from spinning,” Mr Lyons said.

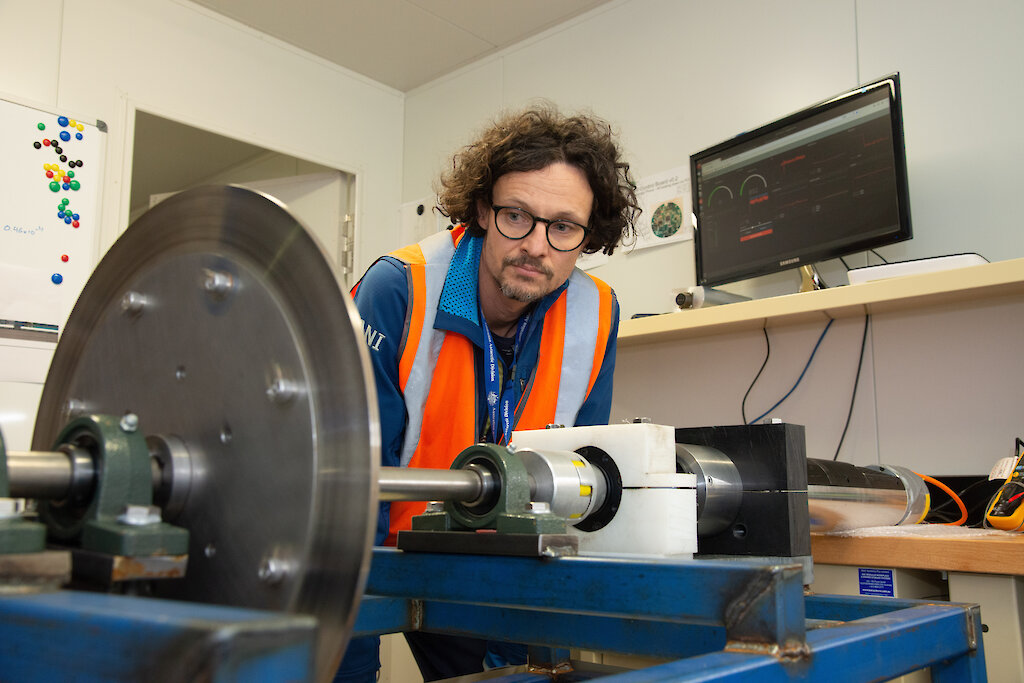

“We’ve now started testing the electronics package – essentially the brains of the system – to see how it operates with the motor and gear box under load.”

The electronics package contains a range of sensors that will provide the drill operator with information on drill speed, temperature, pressure and vibration, and inclination and azimuth data to ensure drilling progresses in a perfectly straight line.

“Our focus has been on how we can engineer the drill to make it as easy as possible for the drillers to extract the ice core, while keeping the hole as straight as possible,” Mr Lyons said.

“They will essentially be drilling blind, so we’ve included as many ‘eyes’ or sensors to help them deal with any challenges they might encounter.”

To mimic conditions at the bottom of the glacier, electronics engineer Lötter Kock, said the Antarctic Division’s instrument workshop rigged up a system that applies braking pressure to the motor and gearbox while the electronics package is driving it.

“The electronics package allows us to communicate what we want the drill to do and then get feedback from the sensors about how the drilling is going,” Mr Kock said.

“We can simulate the toughness of the ice by increasing or decreasing the braking pressure to see how the gearbox and electronics handle it.

“One of our main concerns is to ensure that the drill has enough power to extract itself if it gets stuck in the ice.”

The team has also been testing the rig in the -55°C freezer.

“Everything expands and contracts in the cold and some electrical components don’t like it,” Mr Lyons said.

“We’ve already had instances where solder on the circuit boards we’ve purchased has given way. So now we have to decide whether we want to resolder those boards and re-test prior to deploying into the field, whether the drillers should carry extra boards to swap out if one fails, or whether we can strengthen vulnerable areas.

“To be able to shake down the electronics in this way is essential to ensuring the system is ready to go as soon as we get to Antarctica.”

The drill design team also hopes to add pressure to the drill test.

To drill an ice core, drill fluid is pumped into the hole and flows through and around the drill. This means that as the drill descends, the pressure on it increases in the same way as pressure increases with ocean depth. At 3000 metres, the drill will experience pressures of 300 kilograms per square centimetre.

“Ideally, we’re aiming to develop a pressure vessel that we can put in our freezer,” Mr Lyons said.

They will then work to interface the drill sonde with a winch, cable and drill tower – which moves the drill from horizontal to vertical.

“We need to make sure these three components talk to each other, so we can fully test and evaluate the system before we send it to Little Dome C,” Mr Lyons said.

An “operational test evaluation” is expected to occur near Wilkins Aerodrome, to iron out any issues before the equipment is taken by traverse to Little Dome C, some 1100 kilometres inland from Casey research station.

2 June 2020

The sky is no limit for the future of Antarctic science