Jeffrey Brook, a University of Toronto expert in air quality and health, spent nearly a year reviewing data from Canada’s Joint Oil Sands Monitoring (JOSM) program, which aims to quantify and assess the short and long-term impact of Alberta’s oil sands operations by monitoring air quality, water contamination and biodiversity disturbances.

His findings, recently published in the Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, suggested some air contaminants are not well quantified and that emissions levels for a range of air contaminants – including greenhouse gases – are underestimated.

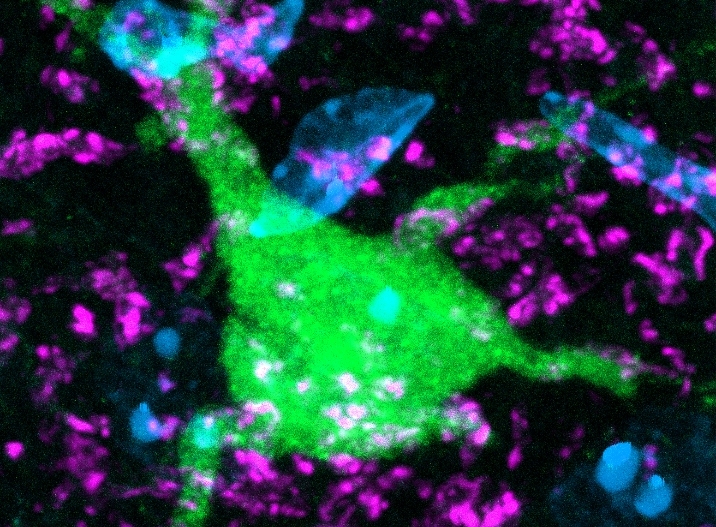

Organic toxins, known as polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs), are also an environmental concern.

“They are in the air, water and the biota and there is evidence that some of the negative changes in the health of some of the species studied are associated with PACs,” says Brook (left), who is an assistant professor in U of T’s Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

While the environmental impact of Alberta’s oil sands industry has long raised concerns in the global scientific community, there have been questions about how to apply the data gathered through initiatives such as JOSM.

Brook’s review – which focused on results generated from Environment and Climate Change Canada’s research on air, water and wildlife contaminants and toxicology – covered the current state of oil sands monitoring in order to identify progress and limitations in knowledge around emissions and potential ecosystem effects. Ultimately, the review aimed to initiate dialogue on areas needing future scientific work.

When it comes to his findings about PACs, Brook stresses that, “Multiple environmental factors are at play. Contaminants from oil sands development is only one of the factors affecting plant and animal species in the area.”

Nevertheless, he also points out that Indigenous populations could potentially be impacted – from changes in their way of life to health effects from exposure to contaminants.

“These risks are presently not well understood, which limits the ability to set short and long-term environmental standards that appropriately recognizes the health and ecological effects.”

Brook says an enhanced monitoring and integrated assessment of the knowledge of oil sands is necessary “to understand its effects and protect important Canadian environments.” That includes northeast Alberta’s Peace-Athabasca Delta, the largest freshwater inland river delta in North America.

Taking stock of lessons learned in oil sands monitoring is also an essential step towards helping to identify potential new areas of study and future policy development.

Brook says a more complete understanding of the oil sands could be on the horizon.

“Tools to predict the current and future impacts of atmospheric emissions on the local and more-distant environment have made a significant leap forward.”