Talk to teens. According to data from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, suicide is the leading cause of death for boys and men aged 10 to 44 years old, and for girls and women aged 15 to 34 years old. The WHO’s LIVE LIFE campaign sets out several effective interventions for suicide prevention: Limiting access to means of suicide; Interacting with the media on responsible reporting; Fostering life and coping skills in young people; and Early identification, management and follow-up. © 2023, Nicola Burghall

Content warning: This press release discusses suicide and self-harm.

The personal yet global struggle with mental health may be more visible now than ever before. Yet many people still find it difficult to access the support they need. In Japan, suicide is sadly the leading cause of death for young people. Researchers, including from the University of Tokyo, have carried out a six-year study to better understand the myriad of factors which can impact adolescent mental health. After surveying 2,344 adolescents and their caregivers, and using computer-based deep learning to process the results, they were able to identify five categories which the young people could be grouped into. Nearly 40% of those involved were classified as groups with some problems. Of these, almost 10% lived with mental health problems which had not been identified by their caregivers. This group were most at risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation. Identifying the factors which may lead young people to suicide and who is most at risk is key to supporting preventive efforts and early intervention.

Last year in Japan, 514 youths and children aged 18 and younger tragically lost their lives to suicide. This was the highest number for this age group since records began in 1978. Suicide is sadly the leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 34 years old, according to data from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. While adult suicide rates have been generally declining over the past 10 to 15 years, the reverse has been noted for adolescents. Officials speculate that school-related issues, difficult personal and family relationships, and lingering impacts of the pandemic may have contributed to the high number of deaths.

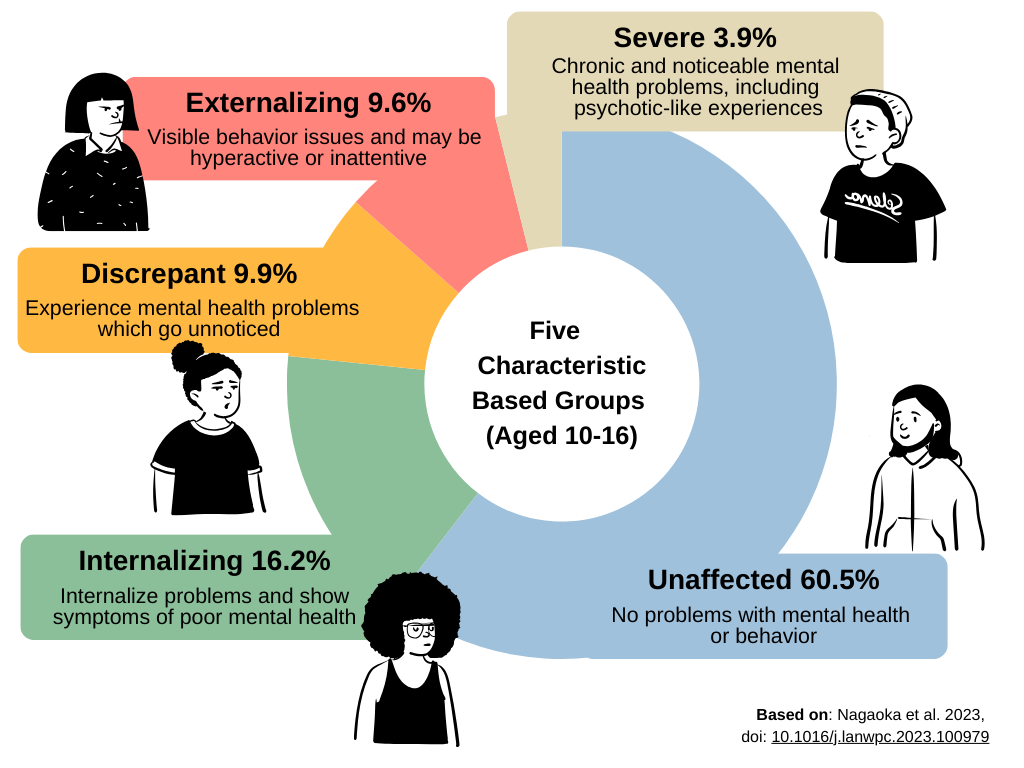

Overview of five groups. Adolescents who fell into the “discrepant” category raised the most concern. In the past, young people who hadn’t clearly or consistently shown symptoms of mental health problems had sometimes been overlooked, as discrepancies between informants’ experiences lead to those problems being underestimated. However, the researchers highlight that monitoring for such discrepancies is very important to help identify adolescents at high risk. © 2023, Nicola Burghall (design elements by Pablo Stanley/Canva)

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies suicide as a major global public health concern, but also says it is preventable through evidence-based interventions and by addressing factors that can lead to poor mental health. Researchers from the University of Tokyo and the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science are analyzing data on various problems in adolescence which were assessed both by self and caregivers, resulting in identification of young people who may be at suicide-related risk.

“We recently found that adolescents who were considered to have no problems by their caregivers actually had the highest suicide-related risk,” said Daiki Nagaoka, a doctoral student in the Department of Neuropsychiatry at the University of Tokyo and a hospital psychiatrist. “So it is important that society as a whole, rather than solely relying on caregivers, takes an active role in recognizing and supporting adolescents who have difficulty in seeking help and whose distress is often overlooked.”

The team surveyed adolescents and their caregivers in Tokyo over a period of six years. The participants complete self-report questionnaires, answering questions on psychological and behavioral problems such as depression, anxiety, self-harm and inattention, as well as their feelings about family and school life. The team also made note of factors such as maternal health during pregnancy, involvement in bullying and the caregivers’ psychological state. The study began when the children were 10 years old, and checked in with them again at ages 12, 14 and 16. Overall, 3,171 adolescents took part, with 2,344 pairs of adolescents and their caregivers participating throughout the full study.

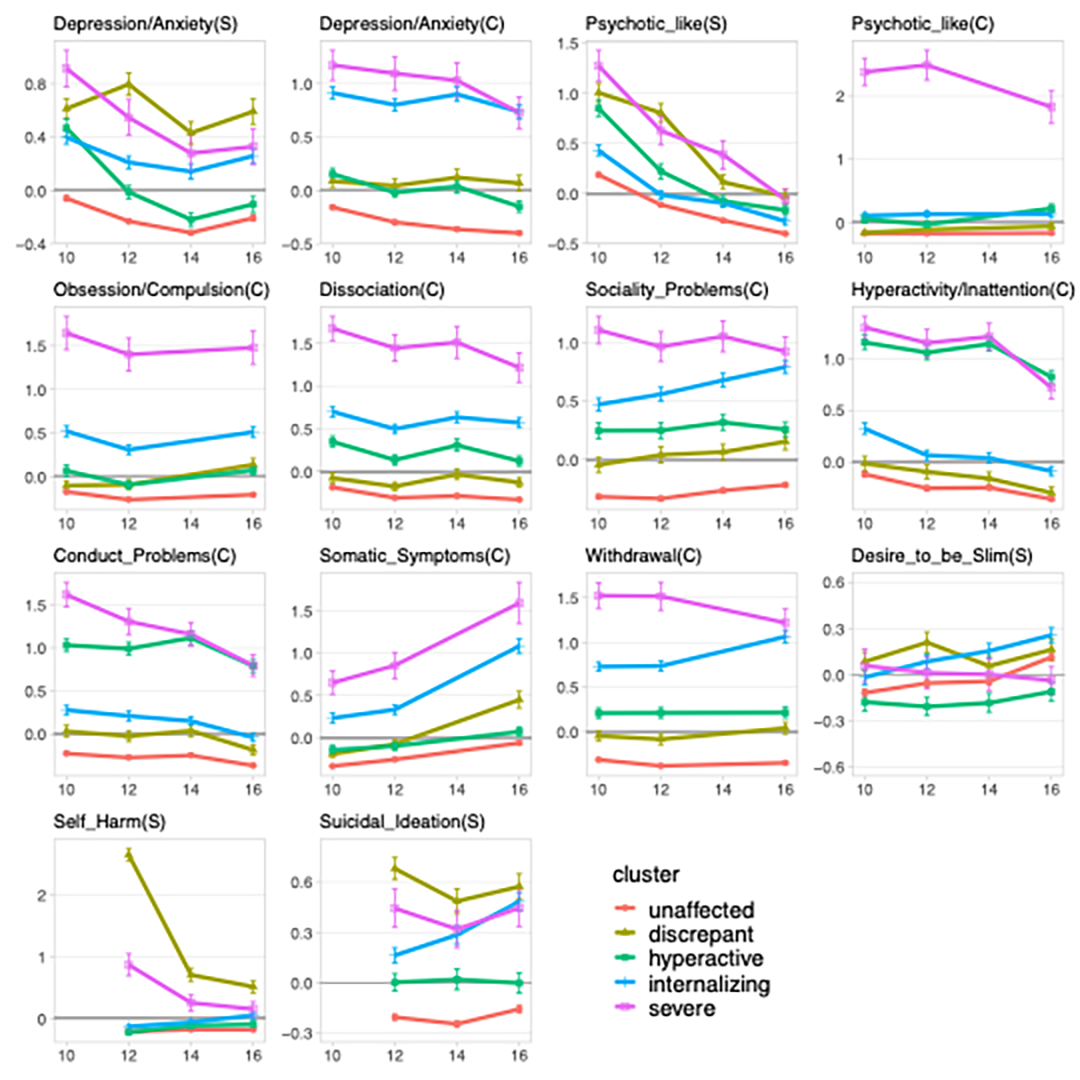

Trajectories for the five groups identified by deep learning. These charts show the average trajectories for the five groups for 14 psychological and behavioral problems. On the vertical axis, higher scores for symptoms indicate greater severity. (S) represents adolescent self-assessment and (C) caregiver assessment. © 2023, Daiki Nagaoka

“Psychiatry faces challenges in understanding adolescent psychopathology, which is diverse and dynamic. Previous studies typically classified adolescents’ psychopathological development based on the trajectories of only two or three indicators. By contrast, our approach enabled the classification of adolescents based on a number of symptom trajectories simultaneously by employing deep-learning techniques which facilitated a more comprehensive understanding,” explained Nagaoka.

Deep learning, a computer program that mimics the learning process of our brains, enabled the team to analyze the large amounts of data they collected to find patterns in the responses. By grouping the trajectories of the psychological and behavioral problems identified in the survey, they could classify the adolescents into five groups, which they named based on their key characteristic: unaffected, internalizing, discrepant, externalizing and severe.

The largest group, at 60.5% of the 2,344 adolescents, was made up of young people who were classified as “unaffected” by suicidal behavior.

The remaining 40% were found to be negatively affected in some way. The “internalizing” group (16.2%) persistently internalized problems and showed depressive symptoms, anxiety and withdrawal. The “discrepant” group (9.9%) experienced depressive symptoms and “psychotic-like experiences,” but had not been recognized as having such problems by their caregivers. The “externalizing” group (9.6%) displayed hyperactivity, inattention and/or behavioral issues but few other problems. Finally, the smallest group was categorized as “severe” (3.9%) and dealt with chronic difficulties which their caregivers were aware of, in particular, psychotic-like experiences and obsessive-compulsive behavior.

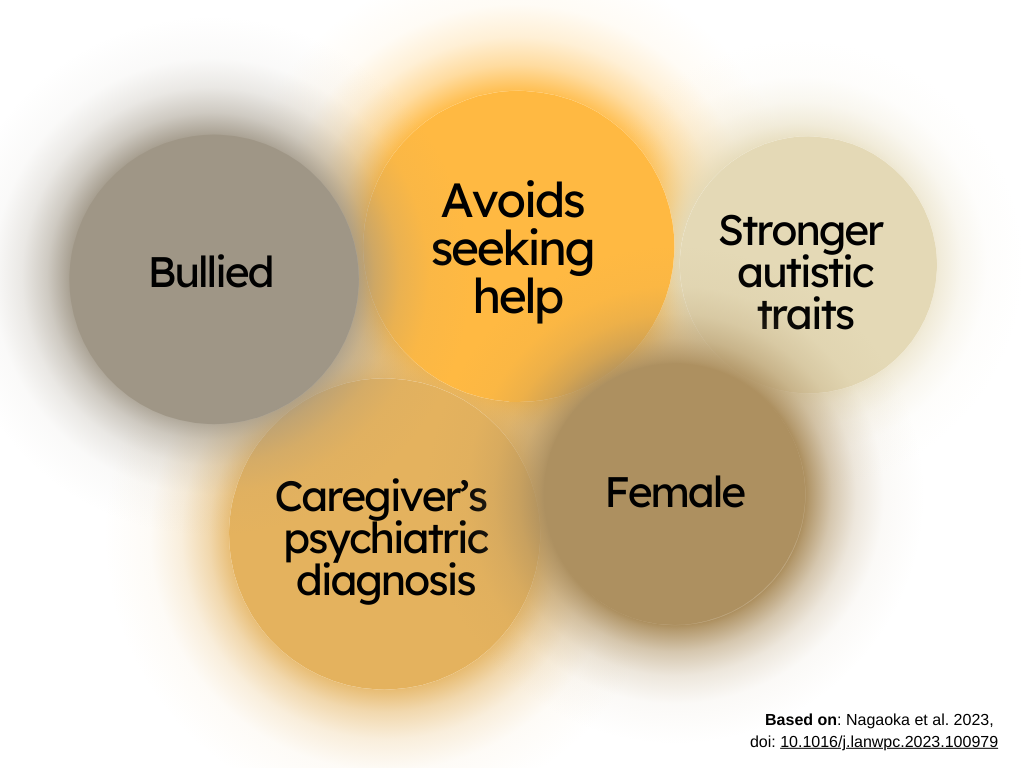

Five key indicators of “discrepant” group membership. Based on the survey of the participants at age 10, children with the above traits and in particular those who didn’t seek help for depression were most likely to be part of the “discrepant” group. © 2023, Nicola Burghall

Of all the groups, young people in the “discrepant” category were at highest risk of self-harm and suicidal thoughts. The researchers found that they could significantly predict who would be included in this group based on if the child avoided seeking help for depression, and if their caregiver also had a mental health problem. The researchers suggest that the caregiver’s mental state could impact the adolescent’s mental health through both genetic factors and parenting environment, such as the caregiver’s ability to pay attention to the difficulties an adolescent might face. Although this research has several limitations, it still enabled the team to identify a number of risk factors which could be used to predict which groups adolescents might fall into.

“In daily practice as a psychiatrist, I observed that existing diagnostic criteria often did not adequately address the diverse and fluid difficulties experienced by adolescents,” said Nagaoka. “We aimed to better understand these difficulties so that appropriate support can be provided. Next we want to better understand how adolescents’ psychopathological problems interact and change with the people and environment around them. Recognizing that numerous adolescents face challenges and serious issues, yet hesitate to seek help, we must establish supportive systems and structures as a society.”

If you or someone you know is struggling, free help and support is available:

UTokyo students can find mental health resources at the Student Counseling Center and the International Student Support Room in English, Chinese and Japanese. / 東京大学の学生は、学生相談所と留学生支援室でメンタルヘルスに関する英語、中国語、日本語の情報や資料を入手することができます。

Tokyo English Lifeline (TELL) provides free and anonymous English-language crisis counseling for people in Japan via phone at 03-5774-0992: https://telljp.com/

Yorisoi Hotline offers free consultations about any problem in Japanese and foreign languages via chat, Facebook messenger and phone at 0120-279-338. For foreign languages, press 2 after the recorded message for a consultation in English, 中文, 한국어/조선어, Tagalog, Português, Español, ภาษาไทย, Tiếng Việt, नेपाली भाषा, or Bahasa Indonesia. / 「よりそいホットライン」では、日本語や外国語で、チャットや Facebook メッセンジャー、電話(0120-279-338)により、無料で悩みを相談できます。外国語(英語・中国語・韓国語・タガログ語・ポルトガル語・スペイン語・タイ語・ベトナム語・ネパール語・インドネシア語)でのご相談は、録音メッセージをお聞きになった後、2番を押してください。

Befrienders International provides confidential support to people in emotional distress or crisis / 国際ビフレンダーズは、精神的苦痛や危機的状況に陥っている方々に匿名での相談を提供します: https://www.befrienders.org/directory?country=Japan

A list of helplines around the world / 世界各国のホットライン・電話相談サービスのリスト: www.suicide.org/international-suicide-hotlines.html

In an emergency, please dial / 緊急の場合は電話してください: 119 to call an ambulance or the fire department; or 110 to call the police (Japan only)/ 119番:救急車や消防車、110番:警察(日本国内用)