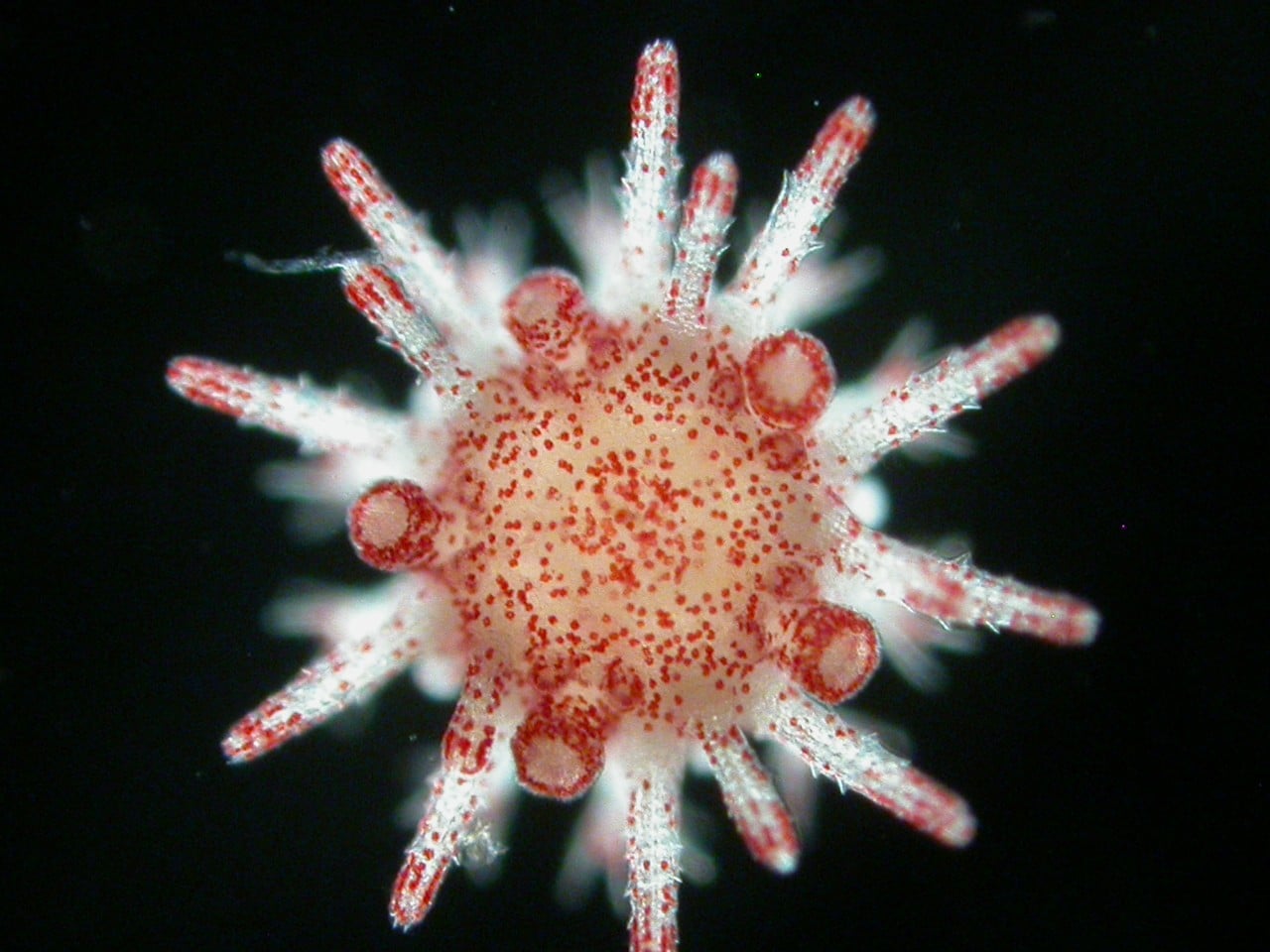

The ability of urchin parents to pass on benefits to their offspring after exposure to heatwaves is key to helping prepare and protect the next generation. (Image: Dr Maria Byrne, Heliocidaris juvenile under microscope_

New research from the University of Sydney and University of Hong Kong studied whether adult sea urchins (Heliocidaris erythrogramma) – exposed to marine heatwaves – could pass beneficial protective mechanisms in their genes to their offspring, potentially ensuring survival of the next generation.

The research, published in Global Change Biology, identified that the ability of urchins to survive extreme conditions through physiological adaptation, and pass on this resistance to the next generation, fundamentally depends on their heat tolerance limits.

Professor Maria Byrne, from the Sydney Institute of Marine Science at the University of Sydney said: “When exposed to thermal stress, some urchin species have the ability to pass on protective mechanisms to their offspring as a means of defence should the offspring come up against the same type of stress as their parents. However, whether these ‘carryover effects’ remain effective throughout the development and growth of the juvenile urchins, and therefore allowing them to survive to become adults, can vary widely.”

“The bottom line is if it stays hot for too long or the heat wave persists, heat hardening of the parent can’t provide long term protection to offspring, but if the conditions return to normal then the offspring of parents exposed to the heat cope with the heat and do well for a short period.”

The researchers also identified that different life stages can have very different abilities to cope with thermal stress; so, the responses seen in offspring may be different to that observed in their parents.

The study exposed adult sea urchins to different marine heatwave scenarios (moderate or strong) and then spawned the adults under these conditions. The offspring were then reared across a range of temperatures and their development was tracked to assess for carryover effects from the parents to their offspring. Surprisingly, heatwave conditioned parents produced faster growing, larger & more heat tolerant offspring. If heatwaves continued, however, there was high mortality in offspring.

Lead author Dr Jay Minuti from the University of Hong Kong said: “If a marine heat wave occurs during the spawning period of the urchins these carryover effects could lead to increased survival of the juveniles under what would normally be stressful temperatures. But, if the heatwave continues throughout the larval development, these short-term physiological responses may lead to higher mortality and ultimately reduce the survival of the next generation.”

“Therefore, as these types of extreme events become more frequent and intense under climate change, the beneficial carryover effects of parental conditioning to marine heatwaves will only protect the more sensitive juvenile stage and enhance survival if ocean conditions return promptly to normal temperatures,” he said.

Dr Bayden D. Russell from The Swire Institute of Marine Science and Area of Ecology and Biodiversity at the University of Hong Kong said: “These findings are really key for our understanding of what some marine ecosystems might look like under climate change.”

“Sea urchins play a key role in maintaining the function of ecosystems, so if the parents can help their offspring survive the extreme temperatures in marine heatwaves, then this may help overall ecosystem function. If these heatwaves continue though, then it is becoming clear that they will devastate these important ecosystems.”

Professor Maria Byrne added: “The species of urchin that we used, Heliocidaris erythrogramma, is native to Australia and is ecologically important in near shore areas. Its fast development is key to its success in nature, but also provides opportunities for trans-generational research to understand how marine species might adapt to climate change.”

With many species of Heliocidaris urchins being ecologically and economically important worldwide (including in Hong Kong), this research provides a first key insight into how the next generation could be protected by their parents from the negative effects of extreme temperatures caused by climate change.

Sea urchins play a key role in maintaining the function of ecosystems, but the fate of future populations is under threat due to increases in the occurrence of marine heatwaves. (Image: Dr Maria Byrne, Heliocidaris population in Sydney, Australia)