The secrets of ageing have been revealed in largest study on longevity and ageing in reptiles and amphibians published today in Science.

The US-led international research provides the first comprehensive evidence that turtles in the wild age slowly and have long lifespans, and that reptiles and amphibians have highly variable rates of ageing – including several species that essentially do not age.

The research by a team of 114 scientists, led by Penn State and Northeastern Illinois University in the US, is the most comprehensive study of ageing and longevity to date – comprising data collected in the wild from 107 populations of 77 species of reptiles and amphibians worldwide, including long-running Flinders University research on Australian sleepy lizards (Tiliqua rugosa).

Interestingly, the team observed negligible ageing in at least one species in each of the ectotherm groups, including in frogs, salamanders, lizards, crocodilians and turtles.

Flinders University Professor of Biodiversity and Ecology Mike Gardner says sleepy lizards have a longevity of up to 50 years or more – which he deems ” ‘negligible’ given most animals (95%) in the study are not alive past that point”.

“However, these data are estimates as it seems the long-term nature of the study hasn’t gone past the point where all animals alive when it started are now dead,” he adds.

The Flinders University dataset is based on the life’s work of the late Professor Michael Bull and Dale Burzacott, and now Professor Gardner, whose continuous research is approaching 40 years – much of it funded by the Australian Research Council.

“Longitudinal research is responsible for many research findings, such as the monogamy and host-parasite relations in sleepy lizards. These long-term datasets underpinning animal lifespans are also vital for reptile conservation efforts,” says Professor Gardner, who is also part of the Evolutionary Biology Unit at the SA Museum.

At 190-years-old, Jonathan the Seychelles giant tortoise recently made news for being the “oldest living land animal in the world”.

Although, anecdotal evidence like this exists that some species of turtles and other ectotherms – or ‘cold-blooded’ animals – live a long time, evidence is spotty and mostly focused on animals living in zoos or a few individuals living in the wild.

The team’s findings call into question what was previously understood about ageing in these animals and could inform future studies of ageing in humans.

The results also may inform conservation strategies for reptiles and amphibians, many of which are threatened or endangered.

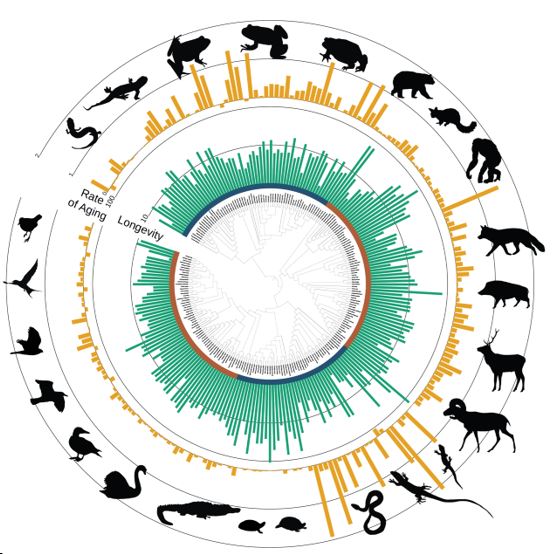

Supertree of all endothermic and ectothermic species included in this analysis. Branch lengths are not scaled. The red in the inner circle represents endotherms and blue represents ectotherms, as throughout the paper. Green bars are longevity estimates and orange bars are the aging rates. Silhouettes from Phylopic.org.

Among their many findings, the researchers documented for the first time that wild ectotherm tetrapods exhibit greater variation in ageing rates and longevities than birds and mammals.

They also found that turtles, crocodilians and salamanders have particularly low ageing rates and extended lifespans for their sizes.

The team found that most wild turtles have slow ageing.

“It could be that their altered morphology with hard shells provides protection and has contributed to the evolution of their life histories, including negligible ageing – or lack of demographic ageing – and exceptional longevity,” says Professor Anne Bronikowski, co-senior author from Michigan State University.

Senior author Associate Professor David Miller, an expert in wildlife population ecology at Penn State, says that the ‘thermoregulatory mode hypothesis’ suggests that ectotherms – because they require external temperatures to regulate their body temperatures and, therefore, often have lower metabolisms – age more slowly than endotherms, which internally generate their own heat and have higher metabolisms.

The protective phenotypes hypothesis suggests that animals with physical or chemical traits that confer protection – such as armour, spines, shells or venom – have slower ageing and greater longevity.

The team documented that these protective traits do, indeed, enable animals to age more slowly and, in the case of physical protection, live much longer for their size than those without protective phenotypes.