The storm in fall 2020 brought more than just torrents of wind and rain. Biting midges, no wider than a few millimeters, were swept up as the storm rolled to the Northeast. Deposited at their new northern home, the midges – Culicoides midges – went back to doing what they do best: biting deer.

Soon deer in New York’s Hudson Valley started showing symptoms of epizootic hemorrhagic disease spread by the midges: weakness, bruising, swollen tongue and loss of fear of humans.

A field biologist with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) quickly contacted Elizabeth Bunting, wildlife veterinarian and associate professor of practice at the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). They’d found a buck exhibiting suspicious symptoms and would bring it in for testing.

The New York State Wildlife Health Program was ready to confirm the diagnosis. A key partnership between Cornell and the DEC, the program coordinates responses when disease strikes New York’s wild animals. And it helps prevent outbreaks, in domestic animals and people too, by translating data into policy.

Wildlife veterinarian Elizabeth Bunting co-founded the Wildlife Health Program and is associate professor of practice at the College of Veterinary Medicine. At her desk is a bison skull.

Bunting knew the disease could spread not only to wild deer but also to captive herds and cattle. She alerted partners across the state about the outbreak, through the Wildlife Health Program’s robust communication network. Ultimately, the disease killed only about 1,500 wild deer that fall, out of a population of one million. In comparison, other northern states have fared much worse and have lost tens of thousands of wild dear to outbreaks of the disease.

“Because of climate change, we are seeing more insect-borne diseases moving into New York,” Bunting says. “Collecting data from these outbreaks helps us to investigate the why, how and where so that the agency can make sound management decisions.”

In April 2021, the DEC renewed the Wildlife Health Program for a third five-year contract, this time for $6.4 million.

“Our program is the best of its kind and has served as a model for other states,” says Kevin Hynes, DEC program leader and wildlife biologist. “We are entering our second decade of this joint endeavor, which combines the expertise and capabilities of both the DEC and Cornell to help protect New York’s wildlife populations and human residents.”

A knowledgeable network

The Wildlife Health Program develops high-quality scientific information about disease ecology in wildlife species through surveillance and research, via the program’s network of DEC field biologists and managers, veterinarians, and collaborating scientists. The program examines 1,600 wildlife cases each year. They generate and centralize diagnostic data, perform epidemiological modeling, advise on health-related policy, and make it all easily accessible to the state and public.

For instance, if a field biologist recovers several diseased crows, they can send them to one of three labs – Cornell’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center in Ithaca, the Cornell University Duck Research Laboratory on Long Island or the DEC’s Wildlife Health Unit in Delmar – that analyze the cause of death. Is it an avian reovirus, which can spread throughout crow populations in winter when they’re in close quarters? If it’s not, the program can sound the alarm if a new disease has emerged.

And the program takes a “One Health” approach – the concept that humans, animals and the planet are interconnected. “If there’s a disease that kills wildlife, we care for the sake of that animal population and its interconnected role in the ecosystem,” Bunting says. “But we also care in case that disease affects domestic animals or even people, whether directly or indirectly.”

Zoonotic diseases – those that animals transmit to people – like West Nile Virus, rabies, tularemia and Lyme disease, can have significant negative consequences for humans. But it works both ways.

Sometimes human activities are the No. 1 cause of death in wildlife: vehicle strikes, birds flying into windows, poisoning, habitat loss and domestic pet attacks. Humans can spread some wildlife diseases by moving animals, feeding them or tracking in the disease via shoes and equipment – like the fungus that causes lethal white nose syndrome in bats. “It is important to have a program in place to detect new disease occurrence and to study the effects and consequences of those diseases,” Hynes says.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic is an excellent example of how complex that can be, Bunting says. “Humans have caught coronaviruses from animals several times in the past. But this time we’ve given SARS-CoV-2 to wildlife, and now there is concern that it could bounce back into humans in a different form.”

A decade of data

In 2011, Bunting and Krysten Schuler, assistant research professor at CVM, created the Wildlife Health Program in partnership with the DEC.

At that time, the DEC had weathered many wildlife disease crises, including West Nile Virus, chronic wasting disease and white nose syndrome, but without any veterinary staff in the agency. Partnering with CVM was a natural fit.

“They came to Cornell because our Animal Health Diagnostic Center had assisted them with detecting and eliminating chronic wasting disease in deer, and diagnosing white nose syndrome in bats,” Bunting says.

Schuler, a wildlife disease ecologist, provided the perfect complement to Bunting’s expertise in clinical wildlife veterinary medicine. “There could not have been anybody better,” Bunting says. “She had years of experience in investigating wildlife disease outbreaks all over the country.”

Bunting, Schuler and the DEC outlined what would be needed to achieve the program’s goal: an accurate, robust and efficient wildlife disease surveillance program.

The first 10 years of the Wildlife Health Program revolved around five pillars: training, surveillance, communication, policy and outreach.

Staff, environmental conservation officers and partners learned safe practices when interacting with or handling wildlife in the field – a crucial step as biologists submitted wildlife cases to create a baseline of information.

“That first year we tested every animal we received for rabies, even deer,” Bunting says. “We found eight deer carrying rabies, which was unexpected. They didn’t fit the typical descriptions of rabid animals. It really landed with our biologists that they had to be careful.”

Communication is key

To improve communication, the program’s data analyst, Nick Hollingshead, helped create a statewide disease database, adapting specialized software and designing a website to make surveillance data accessible to all DEC biologists.

“We needed to be able to share this information back to the agency in a useful way,” Schuler says.

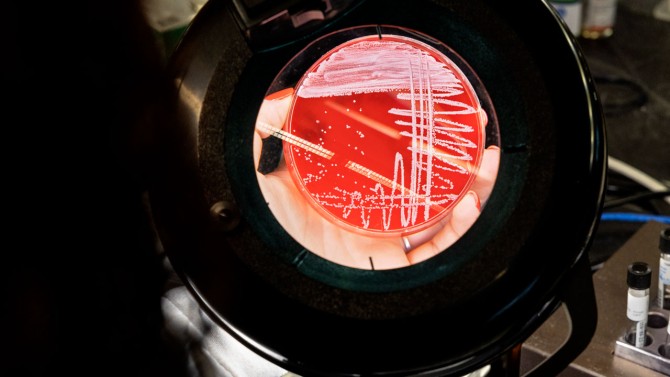

A strain of staph infection from a donkey joint fluid sample is examined at the Wildlife Health Program in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

The program also forged partnerships with the state’s departments of Health and of Agriculture and Markets, so all partners are informed when an issue arises.

The program also informs policy makers on wildlife health topics, such as chronic wasting disease (CWD). The disease is universally fatal and causes progressive weight loss and loss of brain function. It spreads through direct contact as well as saliva, feces and urine. The prions that cause CWD can bind to soil or be taken up in plants, where they remain infectious for years. It is currently present in 26 states.

Schuler had arrived at Cornell from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center in Wisconsin with a Ph.D. in CWD ecology. She worked on the center’s CWD surveillance and interagency management plan and advised on regulations guiding the importation of deer into the state. In 2019, she addressed the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Natural Resources on CWD and provided scientific testimony, which lead to increased federal funding to state wildlife agencies to work on the disease.

“In New York, we helped design a risk-based weighted surveillance program that improves both collection of samples and our ability to detect the disease,” Schuler says. “We’ve provided that system to more than 20 other states, tailored to their needs.”

On Jan. 5, the National Deer Association named Schuler its 2021 Professional Deer Manager of the Year.

“So far, New York is the only state to have had an initial outbreak of CWD and contained it without further detections,” Schuler says, “and we want to keep it that way.”

Outreach outcomes

The program has also created exhaustive resources for wildlife experts and the public. Their online fact sheets cover approximately 40 wildlife diseases and have been downloaded thousands of times. Other outreach includes social media, news articles, live webinars, and recorded videos and lectures. This information helps people understand the consequences their actions have on wildlife.

Medical technician Rachel Saltus examines a strain of staph infection from a donkey joint fluid sample at the Wildlife Health Program in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

For instance, the program is investigating rodenticide poisoning, which kills rodents but can also sicken and kill animals that hunt and eat them. Hawks, owls and fishers, part of the weasel family, have become collateral damage; more than 70% examined in New York had rat poison in their systems. The program is working with partners across multiple states to see how rat poison affects other species, like bobcats; CVM is using the program’s samples to develop a new diagnostic test for wildlife.

The program is also working on strategies to engage the public about the effects of lead with Katherine McComas, Ph.D. ’00, professor of communication in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and vice provost for engagement and land-grant affairs. “Because there is a potential concern that fragments of lead ammunition can wind up in venison,” Schuler says, “we’re working with the DEC on a campaign to educate hunters about the potential hazards of using lead ammunition.”

The next 10 years

Sampling wild animals is challenging and time consuming, and the program has turned to mathematical models to extract more information from state wildlife agency efforts.

For example, testing from 30 years of Hynes’ bald eagle samples showed that about 20% of the birds die from lead poisoning after scavenging game killed with lead ammunition. Schuler hired Brenda Hanley, research associate and mathematician, who built models on how such losses would impact the bald eagle population.

“Every loss is not just the loss of one animal,” Schuler says. “It’s the loss of that animal’s future reproductive capacity, and the reproductive capacity of every offspring that animal would have had.”

Says Bunting, “Our highest priority will always be taking our information and using it to do something – prevent, detect and respond to diseases – all in support of wildlife and the people of New York state.”

This article is adapted from the original by Melanie Greaver Cordova, assistant director of communications at the College of Veterinary Medicine.