“Every time I crack a skull or chase down a thief, I do it as Duke Cosimo’s right arm,” says Ercole, a 16th-century birro, or police officer, assigned to clean up the streets of Florence under Cosimo de’ Medici’s stern rule.

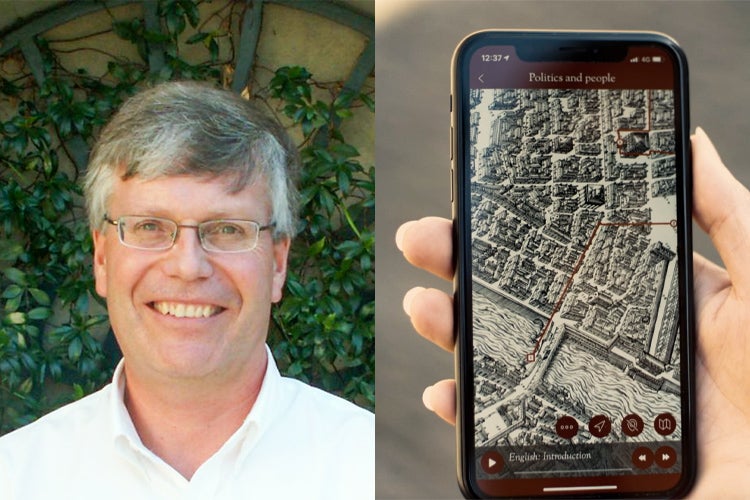

Ercole is one of five historically based, fictional characters in a new location-based app called Hidden Florence, the brainchild of an international team of historians specializing in Renaissance Italy, including Nicholas Terpstra, a professor of history in the Faculty of Arts & Science at the University of Toronto.

The iconic Italian city was one of the most prosperous and powerful cities in Europe during the Renaissance – a key centre of politics, culture and industry. The app takes visitors on a walking tour through Florence’s rich past by linking locations around the city to the lives of 15th– and 16th-century characters who narrate their daily experiences as users navigate the city streets.

For his part, Ercole takes app users on a tour of what he calls “the darker side of Florence,” including locations where criminals were interrogated, imprisoned and executed.

“I’ll show you a side of Florence very few people ever see,” he promises.

Hidden Florence is an app that is the brainchild of Nicholas Terpstra (left), a professor in U of T’s department of history, and an international team of historians specializing in Renaissance Italy

The app’s characters – voiced by professional actors, including James Faulker of Game of Thrones – range from a labourer in the bustling textile industry to an aristocratic widow whose sons were executed for plotting a murder. The players even include Cosimo de’ Medici, the ruler who laid the foundation for generations of the Medici family’s reign over the Florentine Republic.

“The humanities are all about setting individual experiences into the broader contexts of where people live, who they engage with, and what their lives are like,” says Terpstra. The kind of digital mapping on which the app is based “allows us to see connections that we might never perceive when just looking at the words in a manuscript.”

Hidden Florence works with a larger U of T project called DECIMA, the Digitally Encoded Census Information & Mapping Archive – a robust geographic information systems (GIS) mapping tool that collects, digitizes and analyzes historical data on things like human movement and economic activity in Florence during the Renaissance.

The project uses data from three censuses of Florence conducted in 1551, 1561 and 1632, which together comprise one of the richest stores of human data available before the 18th century.

DECIMA is the product of collaboration and innovation by a variety of senior scholars, working with undergraduate and graduate students as well as U of T staff at the Map and Data Library and the GIS Mapping Office, and supported by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

“I’ve always been interested in spaces and places, and how people live in them,” says Terpstra, whose work has delved into GIS as a research and teaching tool, particularly in exploring the spatial, kinetic and sensory dimensions of early modern cities like Florence.

“Digital mapping allows us to take something purely quantitative – like a tax census – and make it a very rich tool for seeing what made a vibrant city work. We’ve been able to draw out voices that are otherwise often obscured, like women, the poor and children.”

Asked whether there is something we can learn from Renaissance Florence, a powerful city-state from more than five centuries ago, Terpstra advises that “amoral and self-serving people will always be around, but individuals can still make a difference. If you want a better society, you have to get involved. Just remember that politics will always be equal parts chess game and knife fight.”

Terpstra credited highly skilled students who transcribed 16th-century Latin and Italian manuscripts, assembled the database and geo-referenced the data since 2011.

“The greatest resources at U of T are the people,” he says. “Two people in particular who have been absolutely vital are Colin Rose, now an assistant professor at Brock University, and Daniel Jamison, who will be continuing to work on DECIMA as a postdoctoral fellow this year. We’ve also benefited from places like the Jackman Humanities Institute, where we had a digital mapping working group running for two years.”

In addition to U of T, partners in the app include scholars from the University of Exeter and the University of Cambridge, as well as funding from the U.K.’s Arts and Humanities Research Council and SSHRC.